On the Draupner oil platform off the coast of Norway, workers would expect big waves to shake things up from time to time. But at 3 pm on New Year's Day in 1995, a monster struck. It made history.

Topping out at nearly 26 metres (about 84 feet), it was the kind of wave you might expect once in a century. The truly baffling part was it came out of nowhere. Now researchers finally have solid evidence of the forces involved in the wave's formation.

A team of engineers from the Universities of Oxford and Edinburgh sent waves criss-crossing in a circular pool in an attempt to create a perfect storm.

"The measurement of the Draupner wave in 1995 was a seminal observation initiating many years of research into the physics of freak waves and shifting their standing from mere folklore to a credible real-world phenomenon," says engineer Mark McAllister from the University of Oxford.

"By recreating the Draupner wave in the lab we have moved one step closer to understanding the potential mechanisms of this phenomenon."

Rogue waves like the one that struck Draupner are quite literally the stuff of legend. For as long as sailors have ventured into the ocean, there have been reports of isolated mountains of water rising out of the blue.

Buoys have measured waves as high as 19 metres out in the lonely expanse of the deepest oceans, while ships have been known to encounter waves nearly 30 metres in height.

But rogues stand out for their spontaneity more than their size. Unlike the kinds of swell whipped up by storms and currents, these waves are born out of the chaos of interfering wave patterns, striking without warning.

The 1995 Draupner wave was a landmark; the first of its kind to be recorded by scientific instruments, making it the subject of investigation for the past two decades.

There are two theories describing the physics responsible for rogues, but which of those best accounts for Draupner has been unclear. So researchers built a miniature version of the monster wave under laboratory conditions to test which kinds of ripples give birth to something truly impressive.

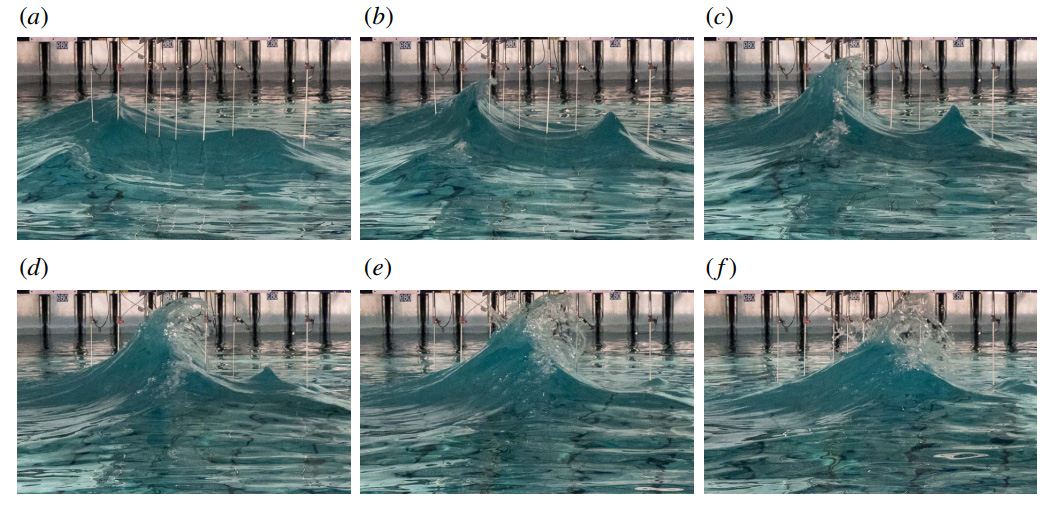

Still photos showing the most successful reconstruction of the Draupner wave. (McAllister et al., Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 2019)

Still photos showing the most successful reconstruction of the Draupner wave. (McAllister et al., Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 2019)

The team conducted their experiment in a circular 25 metre (82 foot) diameter test tank at the FloWave Ocean Energy Research Facility in the UK, kicking up a swell from various angles to find which intersected to form stand-out waves.

They discovered banks of waves crossing at 120 degrees could force an occasional giant to pop up. Without this crossover, environmental conditions imposed a limit on the maximum wave height.

You can check out the movement of the waves in the clip below:

"Not only does this laboratory observation shed light on how the famous Draupner wave may have occurred, it also highlights the nature and significance of wave breaking in crossing sea conditions," says the study's senior researcher, Ton van den Bremer from the University of Oxford.

The mini rogue wave mirrors actual rogue waves photographed on the open seas, making the team confident they were on the right track.

But to the researchers, it also looked uncannily like a classical depiction of famous Japanese artwork.

Even if you don't know much about Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, you've probably seen his work. The 1830 woodblock The great wave off Kanagawa ranks among one of the world's most famous depictions of a breaking wave. Appearing on everything from t-shirts to mugs to wall hangings, it's become an iconic image.

It's impossible to say whether Hokusai actually witnessed such rogue waves or heard them described, and thus created the final artwork based on these impressions.

In fact, it's been suggested that the artist was representing a moment in Japanese history, as the nation stood on the brink of being swamped by Western culture. The breaking of an isolated wave in the open ocean would be the perfect metaphor for a changing Japan.

Intentions aside, the artwork still does a perfect job of illustrating the terrifying nature of rogue waves as unpredictable, destructive forces of nature.

The Draupner oil platform was lucky. Built to withstand waves bigger than the 1995 New Years' Day rogue, it suffered only minor damage.

But many other structures and vessels haven't been so fortunate, with stray encounters causing death and destruction.

Studies such as this one go a long way in highlighting the conditions that make rogue waves more likely, and hopefully, make ocean travel a lot safer.

This research was published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics.