In spite of advances in making laboratory-cultured meat products taste like the real deal, we're yet to see a single factory pumping chicken nuggets out of a vat.

That might not be such a bad thing, according to a recent study by researchers from the University of California, Davis (UCD), and the University of California, Holtville.

They warn current production methods of lab-grown meat could end up being way worse for the environment than beef farming, despite being touted as a sustainable alternative.

Their life-cycle assessment of current meat-growing processes – which has yet to be peer-reviewed – found cultured meat production could emit between four to 25 times more carbon dioxide per kilogram than regular beef and all its hidden costs, depending on the techniques used.

"This is an important conclusion given that investment dollars have specifically been allocated to this sector with the thesis that this product will be more environmentally friendly than beef," UCD food scientist Derrick Risner and colleagues write in their paper.

"My concern would just be scaling this up too quickly and doing something harmful for the environment," Risner elaborates.

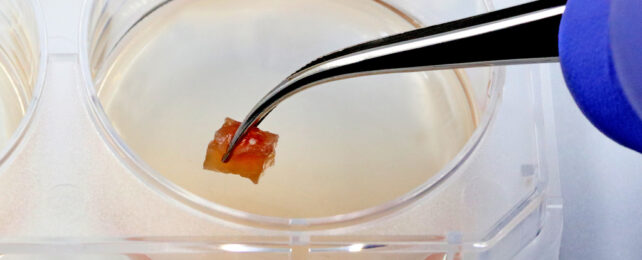

Cultured meat is grown from nonspecific animal cells coaxed into forming tissues we'd be happy to eat, such as fats, muscle, and connective tissues.

While cultured meat uses less land than herds of cattle or flocks of sheep, not to mention less water and antibiotics, environmental costs of the highly specific nutrients required to grow the product rapidly add up.

These include running laboratories to extract growth factors from animal serums, as well as growing crops for sugars and vitamins.

Then there's the energy required to purify all of these broth ingredients to a high standard before they can be fed to the growing meat lumps. This energy-intensive, extreme level of purification is needed to prevent introducing microbes to the culture.

"Otherwise the animal cells won't grow, because the bacteria will multiply much faster," Risner told New Scientist.

It's not all bad news though. Reducing pharmaceutical-grade purification to a food-grade standard should drastically reduce the energy requirements. As a result, greenhouse gas emissions from cultivated meat production could drop to a little over a quarter more than typical beef farming. In best case scenarios, it could be a greener option, being 80 percent better than raising cattle.

Yet the most efficient cattle-grown beef systems that already exist today can still outperform this scenario of cultivating food-grade meat, according to the researchers' estimates.

"It's possible we could reduce its environmental impact in the future, but it will require significant technical advancement to simultaneously increase the performance and decrease the cost of the cell culture media," explains UCD food scientist Edward Spang.

What's more, the researchers' calculations only included the energy costs of making lab-grown meat using current methods, but not the impact of building larger facilities to house large scale production.

Animal cell cultures are a lot harder to grow than bacteria and fungi as they're far more sensitive to their environment. Unsurprising, really, given they evolved to be safely tucked within other protective layers of a body.

This means they require specialized, sterilized, energy-hungry bioreactors to provide the right conditions and protections for these fragile cells.

The researchers say it would make more sense to invest in increasing the efficiencies of existing livestock farms to limit their environmental footprint, which may provide greater emissions reductions sooner that this fledgling industry of lab-grown meat can.

"Given this assessment, investing in scaling this technology before solving key issues… would be counter to the environmental goals which this sector has espoused," Risner and team conclude.

Those improvements better come quick. Overall demand for meat is expected to jump more than 70 percent by 2050 and livestock farming currently represents about 15 percent of all current human greenhouse gas emissions, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Alas, for those of us who would sorely love a more sustainable meat alternative, it looks like plant proteins are still the most viable option.

But if more of us just reduced our meat consumption rather than eliminate it entirely, which is also great for our health, we could still drastically reduce the environmental impact of our flesh-eating habits together.

The research can be found on the preprint server bioRxiv.