In September 2018, a San Diego lab worker was undergoing training for her new job. She would be working with Vaccinia virus (VACV) and, as part of her occupational health and safety session, was offered a vaccine for smallpox in case she was accidentally infected.

She declined.

Just three months later, after injecting a genetically modified version of VACV into the tail of a particularly wriggly mouse, she accidentally poked herself with the needle – and we think she might have suddenly regretted her former decision.

Vaccinia virus is part of the pox family, which includes smallpox, a deadly disease that we finally eradicated in 1980. VACV was used to create the vaccine for smallpox, and it is still used today in labs to help deliver genes into biological systems.

Humans make mistakes, though, and people do occasionally get infected with stray viruses when working in labs. Even so, this lab worker really got the rough end of the stick.

After the injury, she went straight to her supervisor, and went to the emergency department at their request.

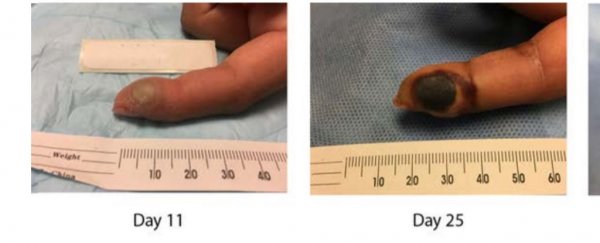

Although she continued to be treated, by day 10 her finger was looking very swollen (which you can see above), and she wasn't feeling well.

"On day 12, she was treated at a university-based emergency department for fever (100.9°F or 38.3°C), left axillary lymphadenopathy [swollen lymph nodes], malaise, pain, and worsening edema of her finger," a case report explains.

"Health care providers were concerned about progression to compartment syndrome (excessive pressure in an enclosed muscle space, resulting from swelling after an injury), joint infection, or further spread."

On that day, she received vaccinia antibodies (to try and help her immune system fight the virus), as well as a virus inhibitor called tecovirimat. The researchers explained this is the first time this has been used in this type of infection.

Although her fever and lymph node inflammation subsided within 48 hours of treatment, her finger was only going to get worse before it got better. You can see the progress below.

The authors of the case report conclude that lab practitioners working with these sorts of viruses need to be aware of the pathogens they are handling, and be sure to understand the risks of an accidental needle prick.

The laboratory worker in this case had to take four months off work to make sure she didn't spread the virus, and admitted she didn't fully understand just what was at stake when she refused the vaccine offered to her.

"Although the patient had declined vaccination when it was initially offered, during this investigation she reported that she did not appreciate the extent of infection that could occur with VACV when vaccination was first offered," the team explains.

"This investigation highlights the misconception among laboratory workers about the virulence of VACV strains; the importance of providing laboratorians with pathogen information and post-exposure procedures; and that although tecovirimat can be used to treat VACV infections, its therapeutic benefit remains unclear."

The paper has been published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.