Chains of up to a dozen carbon atoms have been detected in what appears to have been an ancient lakebed on Mars, contributing to a growing library of compounds that could be a vital clue about the history of life on the red planet.

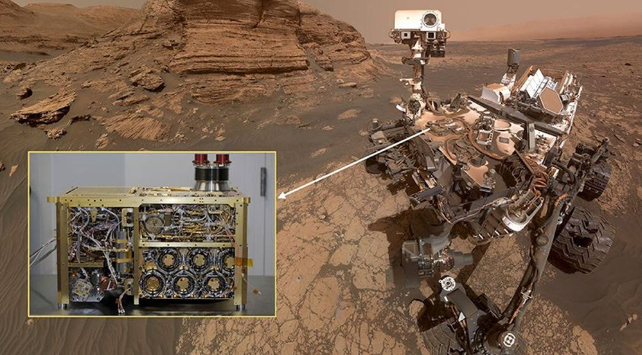

The finding was made by a sampling instrument on NASA's Curiosity rover, with an international team confirming the results in a laboratory here on Earth. The research was led by analytical chemist Caroline Freissinet from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

While the compounds themselves could have been constructed by non-living processes, the very fact they exist at all demonstrates the rover's ability to identify long organic molecules on the Martian surface that may have formed billions of years in the past.

"The fact that fragile linear molecules are still present at Mars' surface 3.7 billion years after their formation allows us to make a new statement: if life ever appeared on Mars billions of years ago, at the time life appeared on the Earth, chemical traces of this ancient life could still be present today for us to detect," Freissinet explained to ScienceAlert.

Curiosity's primary goal is to collect clues that could tell us if Mars ever had life, or if it ever came close.

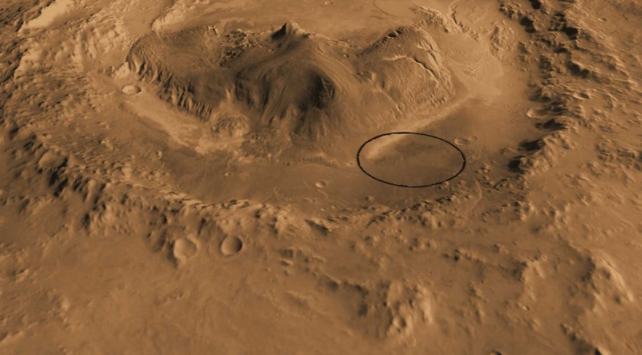

The rover's steady creep over Gale crater's sedimentary rocks has brought it in contact with a number of curious deposits that include various chlorinated and sulfur-containing organic compounds and nitrates, flagging the possibility more complex indicators of life could also be found in the ancient rock.

The researchers used an experimental procedure involving a chemical enhancer to analyze mineral samples taken from a hole drilled into a mudstone deposit named Cumberland.

The experiment's conditions allowed them to cook off molecular oxygen to limit the risk of combustion when they cranked the temperature to around 850 °C (1,562 °F) for a gas chromatography–mass spectrometry procedure.

Among the readings were several of the longest chains of carbon seen on Mars to date – miniscule concentrations of saturated hydrocarbon chains in the form of decane (C10H22), undecane (C11H24), and dodecane (C12H26).

The researchers conducted a number of analytical experiments under laboratory conditions to show how Mars-like mineral conditions could generate the carbon chains from other organic compounds, including benzoic acid, which was also present in their sample.

In any case, the sample analysis and the laboratory work both strongly point to sizable strings of carbon molecules being present in the Martian mudstone.

"The detected molecules are 10, 11, and 12 linear carbon chains, known as alkanes or hydrocarbons," Freissinet said to ScienceAlert.

"This differs significantly from previous detection which were aromatic molecules – [which are] circular rings – of maximum six carbons. Circular rings are more stable than linear molecules."

If the compounds were indeed present in the rock, there's every possibility they were 'built' from simpler molecules like hydrogen and carbon monoxide without any support from a living organism.

Yet it is tempting to consider other possibilities, including a breakdown of even more complex compounds that may be signs of biology. Our own bodies, for example, contain a rich variety of carboxylic acids of the very kind that may be preserved in the sedimentary rock.

"Although abiotic processes can form these acids, they are considered universal products of biochemistry, terrestrial, and perhaps Martian," the researchers conclude.

At the very least, we now know our current technology is capable of literally scratching the surface of chemistry on Mars.

We're far from determining whether any kind of life is fossilized, or even persisting, deep beneath the surface in places where water might still seep. That will almost certainly require future missions, but those future missions will be informed by findings just like this.

For the time being, nobody can blame us for indulging in a moment of wonder at the possibility that these long chains of carbon were once linked together in a life form that evolved on another world.

This research was published in PNAS.