Scientists onboard an icebreaker in Antarctica were blown away when they spied a trove of 60 million icefish nests dotting the floor of the Weddell Sea. The bonanza of nurseries – each guarded by a ghostly looking parent – represents the largest known breeding colony of fish.

Autun Purser of the Alfred Wegener Institute was on the bridge of the German icebreaker, called the RV Polarstern, keeping watch for whales when his graduate student, Lilian Böhringer, who was monitoring the camera feed called up to the bridge.

One of the ship's missions was to monitor the seafloor of the Weddell Sea, and specifically, Böhringer was watching a live video feed from the Ocean Floor Observation and Bathymetry System (OFOBS), which is a one-ton camera towed behind the ship.

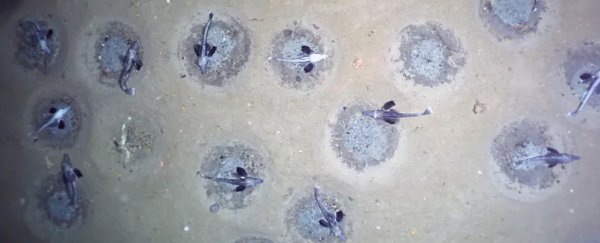

On the video feed, Böhringer could see fish nests pockmarking the seafloor about every 10 inches (25 centimeters) in all directions and covering an area of 93 square miles (240 square kilometers).

"The camera was moving [across the seafloor] and it just didn't stop. They were everywhere," Böhringer told Live Science.

The nests were modest bowls carved in the mud on the seafloor by notothenioid icefish (Neopagetopsis ionah), which are native to the chilly southern oceans. They are the only known vertebrates to completely lack hemoglobin in their blood. Because of this, icefish are considered "white-blooded."

"We realized after ringing up the home institute the next day that we had found something spectacular," Purser said.

After the initial discovery, the team made subsequent passes over the site, towing the camera at a shallower depth to get a wider view of the colony.

Icefish tend to nest in groups, but "the most ever seen before was forty nests or something like that," said Purser. This nesting site, after extensive surveying, has an estimated 60 million nests. "We've never seen anything like this," Purser added.

Most of those nests were attended by one adult fish watching over an average of 1,700 eggs.

The researchers were in the general area because they were studying an upwelling of water that was 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) warmer than the surrounding water. "Our aim was to see how carbon goes from the surface to the seafloor and what communities are in the water column," said Purser.

Intermixed with the nests were fish carcasses. (AWI OFOBS team)

Intermixed with the nests were fish carcasses. (AWI OFOBS team)

Inside the upwelling column of water, they found microscopic zooplankton near the surface, where young icefish, after hatching, swim to feast on the floating buffet before returning to the seafloor to breed. Because of the food, the presence of icefish in the upwelling was to be expected. A breeding colony many orders of magnitude larger than ever seen before, however, was not.

In addition to living fish guarding nests, the team found that the area was littered with fish carcasses as well, suggesting that this massive icefish colony is an integral part of the local ecosystem, most likely serving as prey for Weddell seals.

The discovery of the colony has led to an effort to make it a Marine Protected Area under the international Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

Oddly, the icefish colony seems to have a distinct border. "[The colony] went from very, very dense to nothing, much like penguin colonies," said Purser. "It was like a line in the sand."

That "line in the sand," they found, was the outer edge of the warm upwelling. While more research is needed to determine whether this is coincidental, the upwelling seems to create a rare and ideal environment for the icefish to breed.

Before leaving the area, the crew of the Polarstern left two cameras to observe the inner workings of this rare ecosystem. Purser plans to return to the Weddell Sea in April 2022.

"There's certainly lots to be discovered," said Purser.

This study was published online January 13 in the journal Current Biology.

Related content:

Scientists uncover Antarctic sea creatures 'trapped under ice' for 50 years

Rare wispy ice formations streak across the sea near Antarctica

New expedition will search for Shackleton's Endurance deep below Antarctic waters

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.