If you're reading this, there's a good chance you learned to read as a child in school, but in many countries around the world, illiteracy prevents millions of adults from being able to decipher the written word.

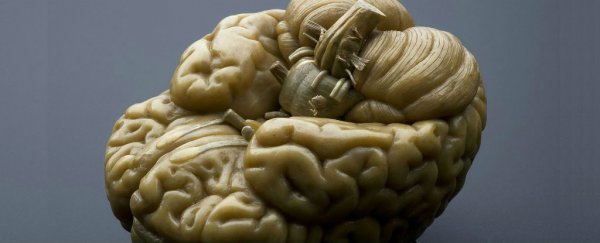

Now scientists have discovered that when people learn to read in their adult years, significant changes take place in their brains – and this rewiring doesn't just show up in the brain's flexible periphery, but also in its deepest regions.

"Until now it was assumed that these changes are limited to the outer layer of the brain, the cortex, which is known to adapt quickly to new challenges", says researcher Falk Huettig from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands.

But brain scans of 21 illiterate Indian women who were taught the script of Devanagari suggest that the process of learning to read goes far deeper than the cortex.

Nearly all of these women were in their 30s, and they had their brains scanned by fMRI machines before learning Devanagari, and six months after.

In half a year, the group had reached a level of literacy comparable with a first-grader, which just goes to show it's never too late to overcome illiteracy, provided you're given the opportunity to learn.

"This growth of knowledge is remarkable," says Huettig.

"While it is quite difficult for us to learn a new language, it appears to be much easier for us to learn to read. The adult brain proves to be astonishingly flexible."

Aside from the progress of their students, what really impressed the researchers was seeing how the learning experience reconfigured the participants' neural connections.

"We found the expected changes in the cortex but we also observed that the learning process leads to a reorganisation that extends to deep brain structures in the thalamus and the brainstem," Huettig explained to Gary Stix at Scientific American.

Specifically, the team found learning to read affected a part of the brainstem called the colliculi superiores, and also the pulvinar (thought to relate to visual attention), which resides in the thalamus.

These deep regions displayed increased functional connectivity with the visual cortex after the Devanagari lessons, which the team thinks is the brain's way of filtering and fine-tuning the flood of visual information that calls for our attention.

In addition to helping us better understand how the brain handles language processing, it's also an eye-opener on the malleability of these deep regions.

"It hasn't been shown before that even these very deep structures in the brain that are evolutionarily old still change fundamentally, and adapt to this new skill, and start to communicate effectively with parts of the cortex like the visual cortex," Huettig explained to Kendra Pierre-Louis at Popular Science.

It's worth pointing out that these results are based on a very small sample of patients – with only 21 learning participants involved in the research, along with nine controls – so we should wait to see if the results are confirmed in later studies.

But the researchers think the findings could help lead to new ways to treat dyslexia, since the condition has previously been linked to the functioning of the thalamus.

And by knowing more about how the brain responds to learning to read – especially for those who only get a chance when they grow up – it will help researchers and educators tailor literacy efforts to those most in need of developing this vital ability.

"The social implications of this kind of research are huge," Huettig told Scientific American.

"We need to understand how flexible the brains of adults are for acquiring a hugely complex skill such as reading later in life to be able to put together literacy programs that have the best chance of succeeding to help these people."

The findings are reported in Science Advances.