An international team of scientists has discovered evidence of common bacteria living so far underground and away from sunlight that we may have to re-evaluate the habitability of deep subsurface ecosystems – including those of alien worlds.

There's a deep terrestrial environment – sometimes called the 'dark biosphere' – that extends hundreds of metres into the ground underneath our feet, where untold legions of hidden microorganisms thrive in ways that scientists still don't fully understand.

Now, for the first time, we have evidence that cyanobacteria, a phylum of photosynthetic bacteria thought to require sunlight to survive, can also live in that dark biosphere.

Originally, these life-forms were not what the researchers were looking for.

Fernando Puente-Sánchez, a microbial ecologist from Spain's National Centre for Biotechnology, was actually looking for other types of bacteria when he examined rock samples taken from a 613-metre (~2,000 ft) deep borehole drilled under the Iberian Pyrite Belt in southwestern Spain.

But instead, he found cyanobacteria, which caused significant worry of having made a major mistake, as he told National Geographic.

"My PhD is going nowhere," he thought, "my adviser is going to kill me."

As luck would have it, the team had found something more interesting than they ever hoped: cyanobacteria (sometimes called blue-green algae), which are found almost everywhere on Earth with at least a small amount of sunlight.

But there was no sunlight – no light of any kind, in fact – in this dark recess more than 600 metres underground.

"What the hell are they doing there?" Puente-Sánchez wondered. "How can they survive?"

The answer, it turns out, relates to hydrogen.

A genetic analysis of the cyanobacteria discovered in this hole in the ground showed they were related to the genera Calothrix, Chroococcidiopsis, and Microcoleus, and the pockets in which the life-forms were found were associated with local decreases in hydrogen concentration.

The team thinks these rock-dwelling cyanobacteria use hydrogen to obtain their energy in the absence of sunlight and oxygen, by shuttling hydrogen electrons to various electron acceptors in the subterranean environment, and getting small amounts of energy in the process.

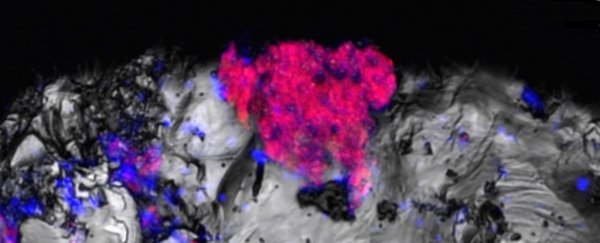

Viable cyanobacterial cells (red fluorescent signals) attached to rock fragments (PNAS)

Viable cyanobacterial cells (red fluorescent signals) attached to rock fragments (PNAS)

The electron transport systems involved have been found in other kinds of cyanobacteria before, but here the researchers suggest they might be leveraged as a de facto survival mechanism, instead of enabling the process of photosynthesis.

While it's only a hypothesis for now, the researchers say it has ties with the abilities of cyanobacteria to survive in other kinds of extreme environments, like deserts and marine systems.

"Some cave-dwelling cyanobacteria survive for long periods in the near-total absence of light, where photosynthesis is no longer possible," the authors write.

"This proposed mechanism relies on traits that are conserved across cyanobacterial lineages, and might thus reflect the lifestyle of the non-photosynthetic ancestor of cyanobacteria."

If they're right, it could point to new understandings about how microbes can survive in rock buried deep beneath the surface. And not just on Earth, but in other kinds of "astrobiological scenarios", such as Mars.

"Our description of this previously unknown ecological niche for cyanobacteria paves the way for models on their origin and evolution," the researchers explain, "as well as on their potential presence in current or primitive biospheres in other planetary bodies, and on the extant, primitive, and putative extraterrestrial biospheres."

That said, Puente-Sánchez is eager to clarify these findings don't mean he's claiming cyanobacteria is lurking unseen under the Red Planet. But it's a fascinating discovery that widens our understanding of how life can thrive in unforeseen conditions.

The findings are reported in PNAS.