Researchers have found evidence of ancient microorganisms that lived in what is now Western Australia at least 4.1 billion years ago. If confirmed, the discovery suggests that life originated on Earth 300 million years earlier than previously thought.

This would mean that life originated not that long after the formation of our planet - just over 4 million years to be precise - which might sound like a really long time, but it's a proverbial blink of an eye in the history of Earth. It would also change our understanding of what it takes for life to form here, and, excitingly, elsewhere in the Universe.

"Life on Earth may have started almost instantaneously," said one of the lead researchers, Mark Harrison, a geochemist from the University of California, Los Angeles. "With the right ingredients, life seems to form very quickly."

The new research also suggests that life existed on Earth prior to the massive bombardment of the inner Solar System - a period of intense asteroid activity which formed the Moon's large craters around 3.9 billion years ago.

It was previously believed that life didn't appear on Earth until after this event, around 3.8 billion years ago. And it was long assumed that before the bombardment the planet was a dry and desolate place that was incapable of sustaining life.

But a growing body of research, including this latest discovery, suggests that this wasn't the case. "The early Earth certainly wasn't a hellish, dry, boiling planet; we see absolutely no evidence for that," said Harrison. "The planet was probably much more like it is today than previously thought."

"Twenty years ago, this would have been heretical; finding evidence of life 3.8 billion years ago was shocking," he added.

If life did exist 4.1 billion years ago, as the new discovery suggests, scientists argue that it may then have been wiped out during the massive bombardment. If this is the case, it means that life on Earth was able to restart itself incredibly quickly. And that means that life could be more abundant in the Universe than we'd previously assumed, says Harrison.

The ancient microorganisms in question were found trapped inside zircons formed from magma in Western Australia. Zircons are heavy, durable minerals that can capture and preserve traces of their immediate environment, just like tiny time capsules.

Harrison and his team analysed more than 10,000 of these zircons, dating back 4.1 billion years, and found some that contained mysterious dark specks. Upon closer inspection, they discovered that these specks had the molecular and chemical structure of ancient microorganisms.

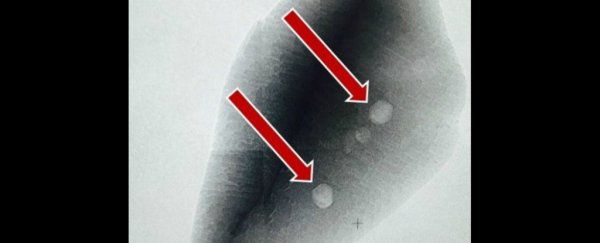

But to confirm that they'd found life, they needed to find traces of carbon, which is fundamental for life. They found that one of the zircons contained graphite - pure carbon - in two locations, shown below,

They were also able to confirm that this graphite hadn't been exposed at all in the last 4.1 billion years, after the zircon formed and trapped it. The team suggests that the graphite - and therefore the microorganism - is older than the zircon, but can't yet figure out how much older.

The results, which have been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, will need to be verified. But Harrison says he's "very confident" that the zircon represents 4.1 billion-year-old graphite.

"There is no better case of a primary inclusion in a mineral ever documented, and nobody has offered a plausible alternative explanation for graphite of non-biological origin into a zircon," he said.

If confirmed, this research will not only change our understanding of life on Earth, but also our perspective when it comes to the hunt for extraterrestrial life. If life does originate quicker than we previously thought, it means that younger exoplanets may already be habitable, and we have more places to look for alien lifeforms. And that's pretty exciting. We can't wait to see what happens next.