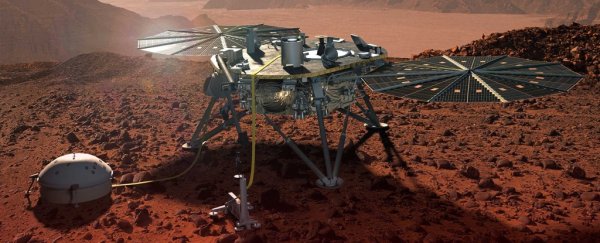

NASA's InSight Mars lander may have recorded its first 'Marsquake' - seismic tremors, faint but unmistakable deep in the belly of the red beast.

Early analysis has confirmed that the tremor did originate inside the planet, as opposed to atmospheric influences such as wind. Now seismologists are hard at work to narrow down precisely what caused it.

Quakes on Mars, just like quakes on Earth, can reveal details about the planet's interior. InSight, which landed on Mars in November last year, is a mission specifically designed to study the guts of Mars. It's equipped with a range of instruments to take measurements of the planet's temperature, rotation and seismic activity.

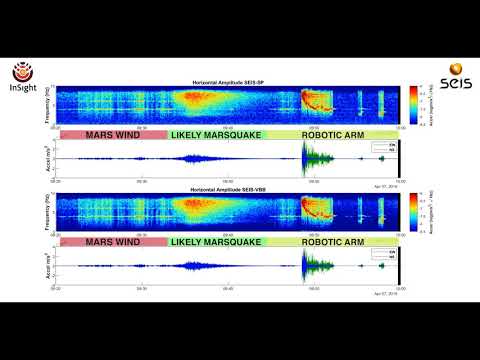

Most of the data collected by the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument to date has consisted of background noise, but on April 6 - Sol 128 of InSight's mission - the instrument finally registered what the team had been looking for.

"We've been waiting months for a signal like this," said SEIS team lead Philippe Lognonné of the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP).

"It's so exciting to finally have proof that Mars is still seismically active. We're looking forward to sharing detailed results once we've had a chance to analyse them."

The waves of a strong enough tremor can act a bit like a planet-sized ground-penetrating radar, only with seismic waves instead of electromagnetic. As these waves propagate through a planet, they can slow down as they move through certain materials, or bounce off others, letting seismologists infer the interior composition.

Sadly, the Sol 128 event was too faint to tell scientists anything about the structure of Mars's interior, and here on Earth it would have been lost among the constant grumblings of tectonic activity.

But it does demonstrate that, even though Mars isn't tectonically active, there is seismic activity - raising hope for a stronger tremor down the line. Especially since three other, fainter seismic signals were also recorded on Sol 105, Sol 132, and Sol 133.

But the Sol 128 signal, as well as being stronger, is interesting for another reason: it bears a strong similarity to the seismic profile of moonquakes detected by surface seismometers between 1969 and 1977 - the devices were stationed there by astronauts from the Apollo missions.

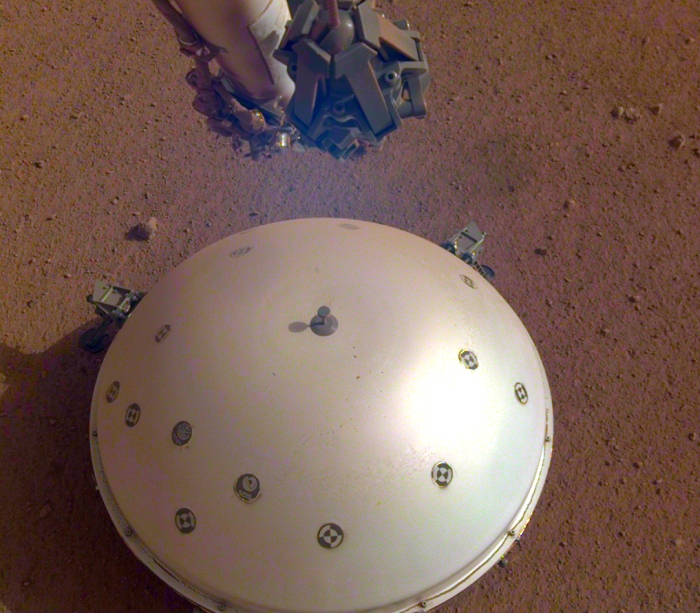

The SEIS instrument. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The SEIS instrument. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Just like Mars, the Moon is not tectonically active. Its seismic activity is caused by a slow, slight shrinking as the interior cools, a process that has been ongoing since its formation 4.5 billion years ago. As the interior shrinks, this creates stresses in the outer crust until it eventually cracks, causing tremors.

Planetary scientists believe that the same type of process is also behind the tremors on Mars.

More detections in the future, and analysis of these detections, will help reveal more. And now we know that SEIS works as intended - a tremendous feat of technical innovation, given how faint the tremors are - meaning it's technology we can continue to refine into the future.

"InSight's first readings carry on the science that began with NASA's Apollo missions," said InSight Principal Investigator Bruce Banerdt of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"We've been collecting background noise up until now, but this first event officially kicks off a new field: Martian seismology!"