The James Webb Space Telescope has given us a view of the earliest moments of galaxy formation in the Universe.

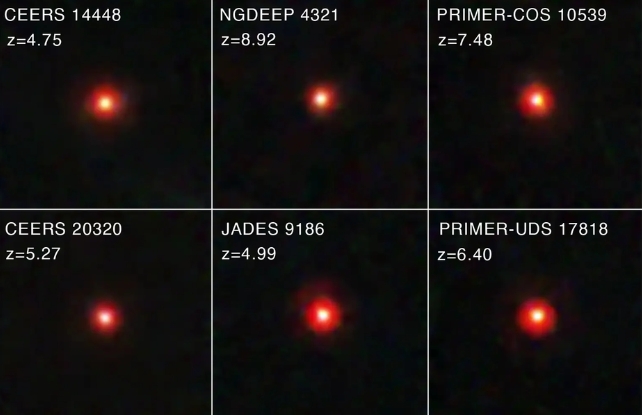

It's also revealed a few surprises. One of these is the appearance of small, highly redshifted objects nicknamed "little red dots (LRDs)."

We aren't entirely sure what they are, but a new study points to an answer.

One of the things we do know about these objects is that their spectra are highly broadened by motional Doppler. This indicates that the gas emitting light is spinning around the central region at a tremendous speed, orbiting at more than 1,000 kilometers per second.

This suggests the material is orbiting a supermassive black hole, which powers active galactic nuclei (AGN). The problem with the AGN model for the little red dots is that their intensity in the infrared spectrum is flat. They also emit very little in the X-ray and radio ranges, which is unusual for AGNs.

To explore this mystery further, this new work looks at 12 LRDs for which JWST has gathered high-resolution spectra. The team then compared the data to models of supermassive black holes.

The models assumed a rapidly spinning accretion disk surrounding the black hole embedded within a young galactic cloud. To begin with, they found that the surrounding cloud would need to be highly ionized. With a dense layer of free electrons surrounding the galaxy, much of the X-rays and radio light would be absorbed.

Of course, if the shroud is dense enough to block X-rays and radio, the black hole would need to be generating energy at a tremendous rate to make the LRDs bright in the red and infrared.

Based on observations, the black holes would have to accrete mass at close to the Eddington Limit, which is the maximum rate for matter accretion. Beyond that rate, the intensity of light produced is so strong that it would push matter away faster than gravity could pull it together.

All of this paints a picture that LRDs are very young supermassive black holes that are quickly growing to maturity. This is supported by estimates of the mass of these black holes in this latest study, which puts them at around 10,000 to 1,000,000 solar masses, which is much smaller than typical supermassive black holes.

This model would also help to explain why we don't see closer LRDs at lower redshifts. Their accumulation of matter at the Eddington limit means they would quickly clear the ionized cloud surrounding them.

As this cloud clears, LRDs would start to resemble the traditional active galactic nuclei we see throughout the cosmos.

Reference: V. Rusakov, et al., JWST's little red dots: an emerging population of young, low-mass AGN cocooned in dense ionized gas, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.16595 (2025)

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.