A symbiotic relationship between two marine lifeforms has just been discovered thriving at the bottom of the ocean, after disappearing from the fossil record for hundreds of millions of years.

Scientists have found non-skeletal corals growing from the stalks of marine animals known as crinoids, or sea lilies, on the floor of the Pacific Ocean, off the coasts of Honshu and Shikoku in Japan.

"These specimens represent the first detailed records and examinations of a recent syn vivo association of a crinoid (host) and a hexacoral (epibiont)," the researchers wrote in their paper, "and therefore analyses of these associations can shed new light on our understanding of these common Paleozoic associations."

During the Paleozoic era, crinoids and corals seem to have gotten along very well indeed. The seafloor fossil record is full of it, yielding countless examples of corals overgrowing crinoid stems to climb above the seafloor into the water column, to stronger ocean currents for filter-feeding.

Yet these benthic besties disappeared from the fossil record around 273 million years ago, after the specific crinoids and corals in question went extinct. Other species of crinoids and corals emerged in the Mesozoic, following the Permian-Triassic extinction - but never again have we seen them together in a symbiotic relationship.

(Zapalski et al., Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 2021)

(Zapalski et al., Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 2021)

Well, until now. At depths exceeding 100 meters (330 feet) below the ocean's surface, scientists have found two different species of coral - hexacorals of the genera Abyssoanthus, which is very rare, and Metridioidea, a type of sea anemone - growing from the stems of living Japanese sea lilies (Metacrinus rotundus).

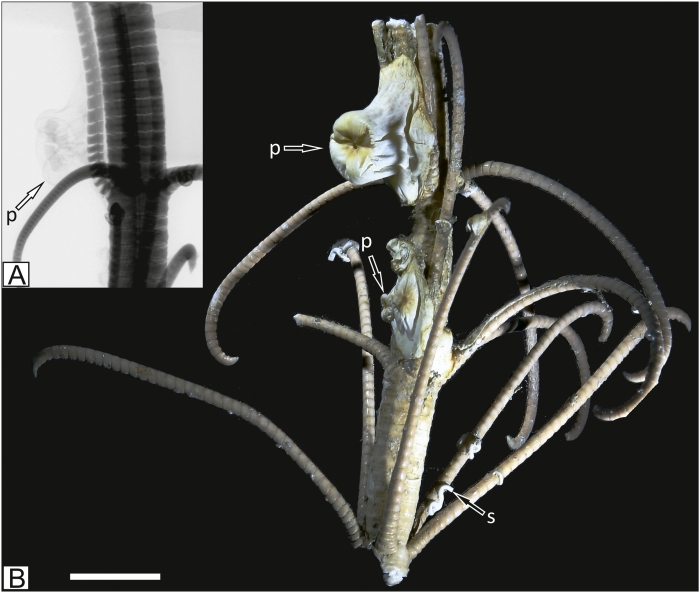

The joint Polish-Japanese research team, led by paleontologist Mikołaj Zapalski of the University of Warsaw in Poland, first used stereoscopic microscopy to observe and photograph the specimens.

Then, they used non-destructive microtomography to scan the specimens to reveal their interior structures, and DNA barcoding to identify the species.

They found that the corals, which attached below the feeding fans of the crinoids, likely didn't compete with their hosts for food; and, being non-skeletal, likely didn't affect the flexibility of the crinoid stalks, although the anemone may have hindered movement of the host's cirri - thin strands that line the stalk.

It's also unclear what benefit the crinoids gain from a relationship with coral, but one interesting thing did emerge: unlike the Paleozoic corals, the new specimens did not modify the structure of the crinoids' skeleton.

This, the researchers said, can help explain the gap in the fossil record. The Paleozoic fossils of symbiotic corals and crinoids involve corals that have a calcite skeleton, such as Rugosa and Tabulata.

Fossils of soft-bodied organisms - such as non-skeletal corals - are rare. Zoantharia such as Abyssoanthus have no confirmed fossil record, and actiniaria such as Metridioidea (seen as a dry specimen in the image below) also are extremely limited.

(Zapalski et al., Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 2021)

(Zapalski et al., Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 2021)

If these corals don't modify the host, and leave no fossil record, perhaps they have had a long relationship with crinoids that has simply not been recorded.

This means the modern relationship between coral and crinoid could contain some clues as to Paleozoic interactions between coral and crinoid. There's evidence to suggest that zoantharians and rugose corals share a common ancestor, for instance.

The number of specimens recovered to date is small, but now that we know they are there, perhaps more work can be done to discover the history of this fascinating friendship.

"As both Actiniaria and Zoantharia have their phylogenetic roots deep in the Palaeozoic, and coral-crinoid associations were common among Palaeozoic Tabulate and Rugose corals, we can speculate that also Palaeozoic non-skeletal corals might have developed this strategy of settling on crinoids," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"The coral-crinoid associations, characteristic of Palaeozoic benthic communities, disappeared by the end of Permian, and this current work represents the first detailed examination of their rediscovery in modern seas."

The research has been published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.