As anyone who has had gastroenteritis will tell you, when human noroviruses hit, they hit hard. However, a new study suggests protection against these dangerous and evasive bugs could be found in an unlikely place: tiny particles produced by llamas.

Like humans, members of the camel family such as llamas (Llama glama) produce antibodies to protect against infection. Within camels and kin, however, these antibodies are much smaller than the ones in our bodies, which is why they're known as nanobodies.

Researchers led by a team from the Baylor College of Medicine tested llama nanobodies against different groups or strains of noroviruses. The GII.4 subgroup is most common in people, and is known for periodically mutating into new variants that are harder to treat.

"We worked with one nanobody named M4, which bound to the predominant GII.4 strain, testing its ability to neutralize different norovirus strains," says molecular biologist Wilhelm Salmen from the University of Michigan.

"That is, to prevent them from infecting human cells."

M4 was tested on 'mini guts', lab-grown stand-ins for human intestines that were infected with GII.4. At very small scales, the researchers saw the llama nanobody interacting with and neutralizing GII.4, as well as its older variants.

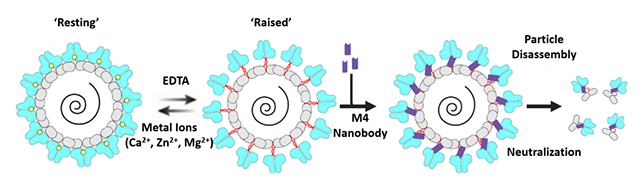

The M4 nanobody appears to identify a hidden 'pocket' in the norovirus that's only exposed when the virus particle 'breathes', alternating between resting and raised structures.

"We think that the raised state is important for the virus to bind to cells and infect them," says molecular biologist Bidadi Venkataram Prasad from the Baylor College of Medicine.

While the raised state enables the spread of the virus, it also leaves it vulnerable. Scientists have reported on this norovirus breathing before, but this new research helps confirm that the shape-shifting is required for infection to occur.

The M4 nanobody appears to be able to jump into this exposed pocket, pushing the norovirus into a more unstable state that's neither resting nor raised. With the virus particles unable to recover, the transmission of the virus is halted.

This research is still at its early stages, and yet to be tested in people, but it's a promising method of attack against viruses that cause hundreds of millions of bouts of sickness a year as well as more than 200,000 deaths, with infants and the elderly particularly at risk.

The team behind the study is hopeful that it will be useful in tackling current and new norovirus strains across the board, as well as informing the way that the dynamics of virus particles are analyzed in vaccine development.

"We discovered that this little nanobody can recognize a part of the norovirus that all the different noroviruses that we tested have in common," says Salmen.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.