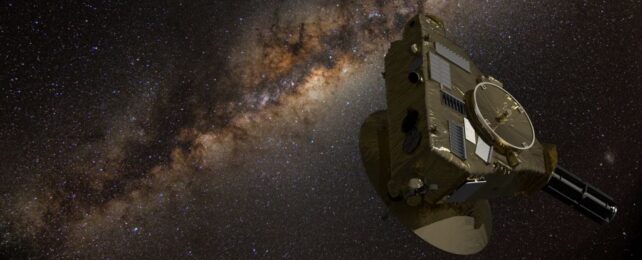

A long, long way from home, a lonely space probe hurtles ever deeper into the darkness of space.

At a distance just shy of 60 astronomical units from the Sun, New Horizons is the most advanced human-built instrument to ever make it so far. This means that we now have a spacecraft that can take unprecedented images of the Universe, unpolluted by the light of the Sun glancing off the interplanetary dust scattered throughout the Solar System.

Now, scientists have measured the true darkness of the Universe, by taking the most precise measurements yet of the faint background of visible light that permeates it. This is the cosmic optical background, and New Horizons' new measurements show that, contrary to previous measurements, there's absolutely nothing strange about it.

"We now have a good idea of just how dark space really is," explains astronomer Marc Postman of the Space Telescope Science Institute.

"The results show that the great majority of visible light we receive from the Universe was generated in galaxies. Importantly, we also found that there is no evidence for significant levels of light produced by sources not presently known to astronomers."

Observing the Universe from within the Solar System is a little bit like trying to see a room from inside a dirty fish bowl. There are elements in the surrounding space we need to correct for, mainly the light of the Sun and the diffuse dust and gas that hangs out between the planets.

For most observations on the interstellar and intergalactic medium, we have ways of working around such obstacles. The spread-out glow of all visible matter in the Universe is simply too faint to extract from the interference within the Solar System.

"People have tried over and over to measure it directly, but in our part of the Solar System, there's just too much sunlight and reflected interplanetary dust that scatters the light around into a hazy fog that obscures the faint light from the distant universe," says astronomer Tod Lauer of the National Science Foundation's NOIRLab. "All attempts to measure the strength of the COB from the inner Solar System suffer from large uncertainties."

NASA's New Horizons probe was sent to study the outer Solar System, including Pluto as part of a flyby in a 2015 and various objects in the Kuiper Belt. Its mission has offered the best opportunity yet to capture the light beyond the fishbowl. At 60 astronomical units from the Sun, there's still a lot of dust, but the Sun's light is faint enough that the cosmic optical background can be measured.

The first attempt at measuring the cosmic optical background with New Horizons' instruments in 2021, however, returned results that were quite weird. Yes, the background was there – but it was much brighter than expected, which scientists struggled to explain.

The new attempt was made in the second half of 2023. This time, the scientists used far-infrared data on Milky Way dust clouds collected by the European Space Agency's Planck mission to calibrate the New Horizons data. This allowed the astronomers to correct for the amount of dust in the Milky Way galaxy.

The results showed that, in the previous analysis, the team had underestimated the amount of dust in the Milky Way, and subsequently overestimated the amount of excess light coming from the rest of the Universe.

The new observations and analysis reveal that, actually, the Universe is emitting as much light as we expect it to, from the sources we expect.

"The simplest interpretation is that the cosmic optical background is completely due to galaxies," Lauer says. "Looking outside the galaxies, we find darkness there and nothing more."

Considering that darkness could be hiding any number of cosmic horrors, that's perhaps not much comfort. But at least we don't need to come up with new physics … for now, anyway.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.