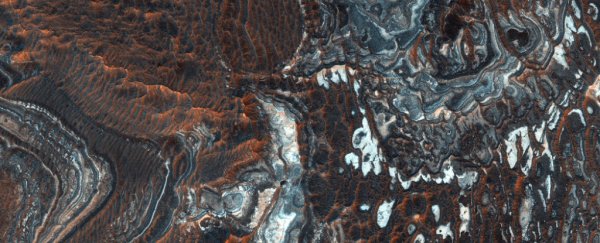

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) delivers once again! Using its advanced imaging instrument, the High Resolution Imaging Experiment (HiRISE) camera, the orbiter captured a breathtaking image (shown below) of the plains north of Juventae Chasma.

This region constitutes the southwestern part of Valles Marineris, the gigantic canyon system that runs along the Martian equator.

The image was originally taken in July of 2007 by the HiRISE camera and showcases three distinct types of terrain. In the top half of the image, this includes plains with craters and sinuous ridge features.

These features are of particular interest since they could be inverted stream channels, which are known to occur when a low-lying area becomes elevated.

(NASA/JPL/UArizona)

(NASA/JPL/UArizona)

There are several reasons why a channel might stand out amid its surroundings, all of which come down to erosion.

For instance, these channels may be formed from larger rocks than their surrounding environment, have been streambeds that became cemented by precipitating minerals, or have become filled with lava at some point.

All of these materials are more resistant to erosion, which means that they would remain and appear elevated after wind or water carried away finer-grained material around them. Other features include plains with exposed layers and layers on the wall of the Juventae Chasma canyon.

Here too, we see evidence of erosion, which has exposed patches of light and dark layers measuring approximately 1 km (0.6 mi) across.

This is made more clear in another image snapped by HiRISE of the adjacent terrain (shown below), where these patches cover two-thirds of the left half of the image.

Here, we see a series of concentric rings that expose deeper and deeper layers of material, the smallest of which is the deepest exposed layer.

(NASA/JPL/UArizona)

(NASA/JPL/UArizona)

While layered terrain is common in Martian canyons, it is not currently known what processes are behind their formation. However, it is believed that the layers in the plains are likely to be made of the same material as the layer in the canyons.

Learning more about these features and how they formed will inevitably reveal more about the geological history of Mars.

Further Reading: University of Arizona/LPL

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.