We all have a wondrous ability to form emotional attachments to many different things, from nature and pets to romantic partners and our children.

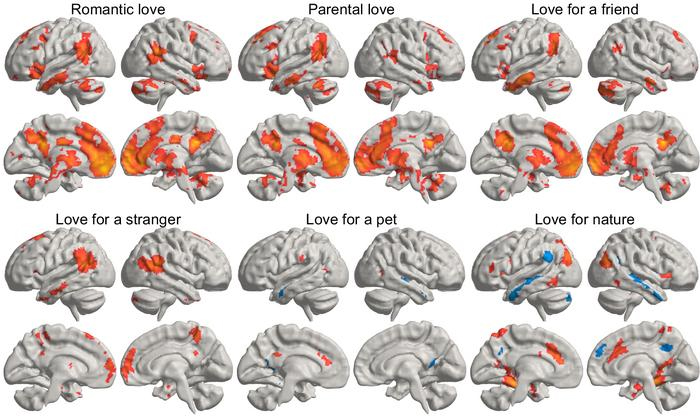

Researchers have now used brain scans to reveal how each of these different types of 'love' have a distinct home in our minds.

Unsurprisingly, the love a parent has for their child produces the most intense brain activity of the love flavors visualized by philosopher Pärttyli Rinne, from Aalto University in Finland, and colleagues.

This was followed by romantic love. Romantic love activates many of the same brain areas in fMRI studies as parental love, as also seen in previous studies, however unlike romantic love, parental love also activates the striatum involved in planning and decision-making and thalamus involved in consciousness and alertness.

"In parental love, there was activation deep in the brain's reward system in the striatum area while imagining love, and this was not seen for any other kind of love," explains Rinne.

This makes a lot of evolutionary sense, given the amount of effort, planning, and decision making required to raise a child.

The researchers also looked at love for a friend, nature, a pet, and a stranger.

All forms of love activated reward centers of the brain, including the superior frontal gyrus, which ties our self awareness with our sensory system, and the cingulate gyrus, which links our actions to emotional response resulting in learning.

But the patterns of expression were different between love types. For example love for strangers activated the same underlying brain processes as the close relationships did, but far less intensely.

"Different types of interpersonal affiliation can thus be seen to form a continuum from closer affiliative bonds to more distant relationships according to the degree of subcortical and cerebellar activation," Rinne and team write in their paper.

Compated with other types of love, a love for nature activated the most different brain areas, yet interestingly it still lit up the cingulate gyrus just like social love types do.

When viewing people's love for pets the researchers could easily distinguish between people who live with pets and those who do not.

"When looking at love for pets and the brain activity associated with it, brain areas associated with sociality statistically reveal whether or not the person is a pet owner," explains Rinne.

"Our result suggests that for pet owners, love for pets is neurally more similar to interpersonal love than for participants without pets," the researchers add.

To capture these images, participants were told a neutral story, such as: imagine you are absent-mindedly brushing your teeth, while their brains were being scanned in an fMRI.

They were then told a simple love story, like: "You see your newborn child for the first time. The baby is soft, healthy and hearty – your life's greatest wonder. You feel love for the little one."

The brain scans between both scenarios were then compared for 55 people from Finland between the ages of 28 and 53. The participants were all healthy, in a relationship, and had at least one child and about half lived with a pet.

At the end of the oral narrative, participants were also shown an image of the story and asked to immerse themselves in the feeling of the narrative, during which their brain activation patterns were similar, only less intense.

"We now provide a more comprehensive picture of the brain activity associated with different types of love than previous research," says Rinne.

While this is the largest study of its kind to date, it is still quite small and limited to one culture.

"Love is a complex and multifaceted set of biologically grounded and culturally modified phenomena," the team cautions. "Further cross-cultural research is still required for a better understanding of how cultural and demographic factors influence various feelings of love and their correlates in the human brain."

The researchers hope that understanding the brain mechanisms behind our experiences of different types of love will help us develop better treatments for attachment disorders and other mental health conditions.

This research was published in Cerebral Cortex.