Unless you're super into typography or have a hand-lettering hobby, you will likely struggle to tell which of the above shapes of the lowercase 'G' is correct (if you're looking at this text, you're cheating).

That's okay. As it turns out, most people are in the same boat, despite having seen this letter millions of times - and this has crazy implications for how we think about our ability to read and write.

Standard thinking in psychology goes that our reading skill is directly tied to our ability to recognise letters. Therefore one would expect we have super-detailed knowledge of each single letter, down to every swirl and loop.

Enter the lowercase letter 'g', and this idea falls apart.

You see, there's more than one way to print this letter, and we're not talking about differences brought about by individual handwriting quirks.

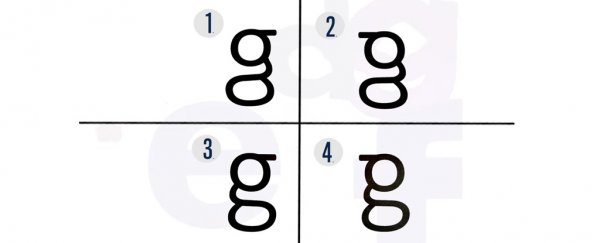

In modern typography, there are two standard ways the lowercase 'g' can be shaped - either as the single-storey or opentail 'g', or the double-storey or looptail 'g'. Here's a picture of them both side by side:

Now, the opentail one doesn't cause any headaches, since it's similar to what people who use the Latin alphabet are taught to write in school.

It's the looptail version of this letter that freaks people out - not only do many not realise there are two distinct print shapes, they also find it hard to recall which shape is the correct one, and most can't draw it even when they know what it should look like.

These were the findings of a team of cognitive scientists from Johns Hopkins University, who tested people's awareness of contrasting letter shapes in a series of three experiments.

In the first one, 38 participants recruited from the university's pool of students were asked a series of questions about their awareness of letters that have different shapes - with surprising results.

"Despite being questioned repeatedly, and despite being informed directly that G has two lowercase print forms, nearly half of the participants failed to reveal any knowledge of the looptail 'g', and only 1 of the 38 participants was able to write looptail 'g' correctly," the team writes in the study.

Pathetic. (Wong et al., 2018)

Pathetic. (Wong et al., 2018)

To follow up on this apparent lack of letter knowledge, the team did a second experiment in which 16 new participants had to read a paragraph, specifically attending to all the lowercase 'g' appearances - printed in the looptail style.

Once the text was taken away, the participants were asked to write the letter 'g' as it appeared in the text they just read.

Again, only one managed to do so correctly. Half of them thought they saw the opentail version, and one even got sassy about it.

"One participant seemed to think that writing opentail 'g' was the only conceivable response to the task: When asked to write the G she had seen, she said, 'This is stupid'," writes the team. Joke's on her.

In the third experiment, the researchers made the whole thing even more straightforward: 44 new participants had to pick the correct shape of either a looptail 'g', or a two-storey 'a'.

Yep. Most of them totally chose the wrong 'g':

(Wong et al., 2018)

(Wong et al., 2018)

"What we think may be happening here is that we learn the shapes of most letters in part because we have to write them in school," said senior author of the study, cognitive scientist Michael McCloskey.

"Looptail 'g' is something we're never taught to write, so we may not learn its shape as well."

According to the team, these findings support the idea that we don't really learn letters down to the fine details, but just enough so we can tell them apart.

Additionally, uncovering these discrepancies shows that there's still a lot we don't understand about how people perceive the world around them - even when it comes to something as incredibly common as letters.

"What about children who are just learning to read? Do they have a little bit more trouble with this form of g because they haven't been forced to pay attention to it and write it?" said McCloskey.

"That's something we don't really know. Our findings give us an intriguing way of looking at questions about the importance of writing for reading."

The study has been published in Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance.