Psychedelics like lysergic acid diethylamide ( LSD) and psilocybin are popular for their use as party drugs, but less so for what researchers claim to be their therapeutic effects - which has been a major focus for a number of clinical trials in the last decade.

Magic mushrooms, for example, have been the focus of some recent work that saw how it could help with treating some of the symptoms of clinical depression.

For instance, a study from the US last year showed how a single dose of psilocybin can lift anxiety and depression felt by cancer patients.

Now, scientists from the Imperial College London have found how psilocybin, which is the active psychedelic compound that occurs naturally in magic mushrooms, can "reset" brain activity in patients suffering from depression.

Their study, which was published in the journal Scientific Reports on Friday, highlights how psilocybin gave patients a "kick start" in fighting clinical depression.

Robin Carhart-Harris/Imperial College London

Robin Carhart-Harris/Imperial College London

The researchers at Imperial gave two doses (10 mg and 25 mg) of psilocybin, with a week in between each dose, to 20 patients with a treatment-resistant form of depression.

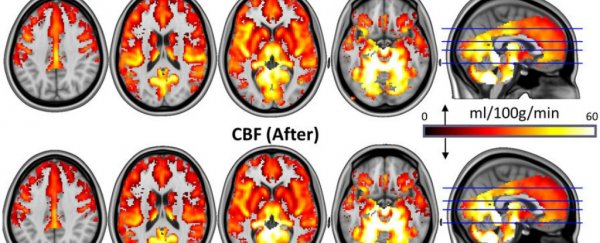

Immediately after receiving the doses, the patients said they felt a decrease in depressive symptoms, which MRI scans of their brains revealed to have been due to a reduce in blood flow to areas involved in handling emotional responses, stress, and fear.

In short, the patients experienced a sort of reboot.

"We have shown for the first time clear changes in brain activity in depressed people treated with psilocybin after failing to respond to conventional treatments," Robin Carhart-Harris, head of Psychedelic Research - there's such a thing - at Imperial, said in a press release.

"Several of our patients described feeling 'reset' after the treatment and often used computer analogies. For example, one said he felt like his brain had been 'defragged' like a computer hard drive, and another said he felt 'rebooted'."

It would seem that during the drug 'trip', brain networks went through an initial disintegration that was followed by a re-integration afterwards, when the patients "come down" from the psychedelic.

"Psilocybin may be giving these individuals the temporary 'kick start' they need to break out of their depressive states and these imaging results do tentatively support a 'reset' analogy. Similar brain effects to these have been seen with electroconvulsive therapy," Carhart-Harris added.

The researchers acknowledged, however, that while their study provides a new window into the brains of people who've taken psychedelics, the small number of patients tested and the absence of a control/ placebo group limits the significance of their study.

"Larger studies are needed to see if this positive effect can be reproduced in more patients," said senior author David Nutt, director of the Neuropsychopharmacology unit of the Brain Sciences division at Imperial.

"But these initial findings are exciting and provide another treatment avenue to explore."

The researchers also warned against self-medicating using such psychedelics.

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.