The decades-long quest to develop a HIV vaccine has been dealt another major blow, with the 'last true candidate in development' failing to prevent infections any better than a placebo in late-stage clinical trials.

The multinational Mosaico study, which began in 2019 and involved more than 3,900 volunteers, was investigating a four-shot HIV vaccine for cisgender men and transgender people who have sex with cisgender men and/or transgender people.

As the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) reported last week, the trial was stopped after a planned data review by the study's independent data and safety monitoring board found the vaccine was safe, but ineffective.

"For our research partners and others who have waged a decades-long effort to develop vaccines to end the HIV/ AIDS pandemic, these results are disappointing," lead investigator Susan Buchbinder, a HIV researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a statement.

"Although HIV continues to prove uniquely challenging for development of a vaccine, the HIV research community remains fully committed to doing just that, and each study brings us a step closer to this realization."

The vaccine was being developed by Janssen, the vaccine arm of Johnson & Johnson, who were trialing the same vaccine delivery system as their now-widely used COVID-19 vaccine.

Despite decades of research, only one vaccine candidate has thus far shown even marginal efficacy in preventing HIV infections. Completed in the early 2000s, it's the largest HIV vaccine trial to date. Researchers were hoping to improve on those results, with a HIV vaccine that offered broad protection.

To do that, the Mosaico trial, and other parallel studies, were investigating vaccines based on 'mosaic' immunogens – snippets of genetic material from multiple HIV subtypes – that are designed to train the body's immune system to recognize the wide array of global HIV strains.

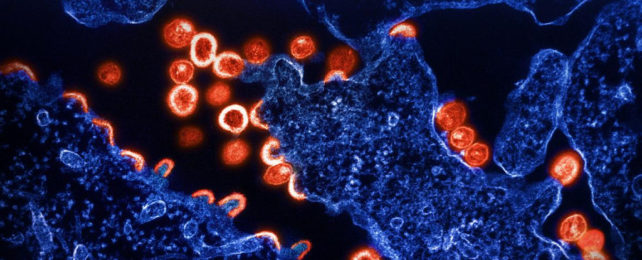

This was thought to be a promising strategy against HIV, a notorious virus that mutates quickly, effectively staying many steps ahead of vaccine development. It also shields itself from being recognized by antibodies with a heavily sugared protein coat.

At the time the trial was launched, Buchbinder said it represented "an important step toward developing a safe and effective HIV vaccine for people worldwide."

That sentiment still rings true, even as the trial comes to a close. Experts say the way the trial valued participants' choice, removed barriers to access preventative medication, and included those most vulnerable to HIV will have lasting benefits.

Volunteers were enrolled in the trial only after they were offered, and declined, antiretroviral drugs that can prevent HIV infection. These preventative medicines, called HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), are taken daily. Those who opted for PrEP were linked into services that supply the medicines, and participants in the trial who later changed their minds and wanted to use PrEP could do so too.

"One thing we've clearly learned from study participants is that people want a choice, and that a vaccine will be an important option for those who don't want PrEP," Buchbinder said.

"The ethical and community-friendly design and conduct of this study has helped to build trust in communities that may not be inclined to trust research institutions," Mitchell Warren, executive director of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, added.

Other efforts to develop HIV vaccines are continuing. Three mRNA HIV vaccines are currently being tested in a phase I clinical trial, which will study whether the vaccines are safe and can stimulate an immune response.

"Finding an HIV vaccine has proven to be a daunting scientific challenge," immunologist and former NIAID director Anthony Fauci said in a statement last year.

"With the success of safe and highly effective COVID-19 vaccines, we have an exciting opportunity to learn whether mRNA technology can achieve similar results against HIV infection."

Trouble is, phase I safety trials are a long way from phase III trials that deliver data on whether a new vaccine (or drug) is effective or not, so it will be many years until we see another candidate reach late-stage trials.

As Warren told health reporter Helen Branswell at Stat News, the latest trial results are a "harsh reminder" of the challenges in developing a HIV vaccine.

At least five experimental HIV vaccines, tested over nine trials, have failed in efficacy trials, Warren said. He suspects the problem lies not in vaccine delivery systems – which have worked against COVID-19 – but in the immune targets that HIV vaccines are trying to hit.

"Our challenge is figuring out exactly what is the target," Warren told Branswell. "We have the vehicles. We don't even know what passengers to put in the vehicles."

A hard task against a shapeshifting virus.