Fructose, a new paper proposes, is the pernicious little demon driving so many human metabolisms towards obesity. Although it's not the biggest source of caloric intake, it does trigger the urge to eat fattier foods, at higher quantities, resulting in overindulgence in food.

A major analysis, led by medical doctor Richard Johnson of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, suggests that a decision to lose weight may not come down to a choice between ditching either carbs or fats, but a case of responsibly reducing both together.

Unfortunately, having significant quantities of the carbohydrate fructose in your diet won't make that so easy.

"Although practically all hypotheses recognize the importance of reducing ultraprocessed and 'junk' foods, it remains unclear whether the focus should be on reducing sugar intake, or high glycemic carbohydrates, or fats, or polyunsaturated fats or simply increasing protein intake," the researchers write in their paper.

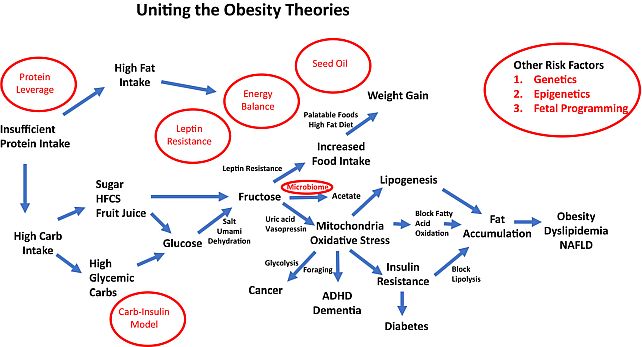

"Here, we review the various dietary hypotheses for obesity. We propose that all of the various hypotheses are largely correct, and that although they outwardly seem incompatible, that they can all be unified based on another hypothesis known as the fructose survival hypothesis."

Fructose is a type of sugar that can naturally be found in fruit. Balanced by the vitamins and fiber therein, your daily apple, banana, and orange isn't so much an issue. The body can also make small amounts of fructose from carbohydrates such as glucose, and salty food.

Added to sweeteners such as table sugar and high fructose corn syrup in high quantities, concentrations of this particular sugar can quickly pile up in our diet, often without our realizing.

Johnson and his colleagues undertook an exhaustive study of all the known contributors to obesity, and found that the metabolism of fructose in the body causes a drop in a compound called adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which provides energy for your body's cellular processes.

When ATP falls to a low enough level, it's a signal to your body that you need more fuel. This makes you hungry, so you eat.

This is what the researchers call the fructose survival hypothesis, and it ties together different theories of what causes obesity, even those that seem wildly incompatible, like fat intake versus carbohydrate intake.

"Essentially, these theories, which put a litany of metabolic and dietary drivers at the center of the obesity epidemic, are all pieces of a puzzle unified by one last piece: fructose," says Johnson. "Fructose is what triggers our metabolism to go into low power mode and lose our control of appetite, but fatty foods become the major source of calories that drive weight gain."

This low power mode activates even if there are fuel reserves at hand. Even when there is plenty of available energy in the form of stored fat, fructose blocks the body from tapping into any of that storage.

In some contexts, that's a good thing. Bears preparing for hibernation can keep their fat reserves intact by chowing down on fruit. But consumption of sugary foods and drinks in humans, the researchers say, is the way towards unhealthy excess.

"This evolutionary-based mechanism is used to assist animals in the storage of fat when food is still available before an expected food shortage," the researchers write. "Although meant to aid survival in the short term, with chronic over-engagement this pathway shifts from being beneficial to driving many of today's modern diseases."

More research is required to determine exactly how this works, since most of the research into how fructose works is based on animals. However, the findings represent an important step in resolving this escalating health crisis.

The research has been published in Obesity.