A species of wasp that lives in Japan seems to have developed a rather unconventional method for warding off attacks.

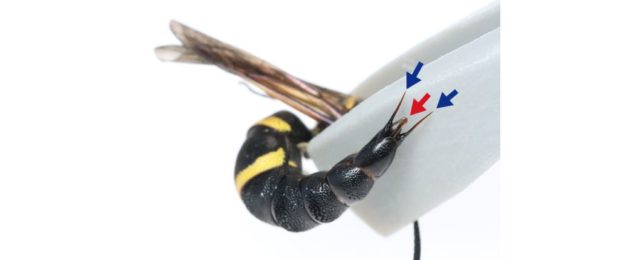

Researchers observed the male of the mason wasp species Anterhynchium gibbifrons using spikes that flank the penis as a weapon – with varying effectiveness – against hungry frogs that think the insect might make a tasty snack.

"This study," write ecologists Shinji Sugiura and Misaki Tsujii of Kobe University in Japan, "highlights the importance of male genitalia as an anti-predator defense and provides a new perspective for understanding the ecological roles of male genitalia in animals."

Some insects of the order Hymenoptera – wasps and bees – can deliver venomous stings as an attack or defense mechanism against prey and predators. However, only females of these species have a venomous sting; when you're stung by a female wasp, she's jabbing you with her ovipositor, which can deliver either venom or eggs as the situation demands.

It's thought that male wasps are harmless, and in some cases, that's true: They do indeed lack the apparatus to deliver a painful sting. But when studying A. gibbifrons – a species discovered in 2015 – Sugiura and Tsuji noticed something strange. When handling a male of the species, it delivered quite a painful prick to Tsuji using spikes protruding near the insect's penis.

Such spikes are seen in some wasp species and are known as a "pseudo-stinger". Intrigued after having been on the receiving end of it, the researchers decided to investigate its function in detail.

In some insects, hooks and barbs can help keep the female from wriggling away during mating. However, in a laboratory setting, the pseudo-stinger of A. gibbifrons played no role whatsoever in amorous proceedings.

The next step was to investigate if the wasps commonly use the equipment defensively. Pond frogs of the species Pelophylax nigromaculatus and tree frogs of the species Dryophytes japonica were recruited, and Sugiura and Tsuji set about observing how the amphibians and insects interacted under a range of conditions.

Seventeen tree frogs were each provided a male wasp. All tree frogs opened their mouths to eat the wasps, which fought back using their mandibles and pseudo-stingers. Ultimately, 35.3 percent of the frogs gave up, and the wasp escaped.

As a control, 17 different tree frogs were provided with a male wasp whose genitalia had been removed. All 17 of those wasps were handily devoured.

Another 17 tree frogs were provided female wasps. Just 47.1 percent of those frogs made a move to eat the female wasps, and most of them gave up after being attacked.

The pond frogs, on the other hand, just straight up didn't care. They ate all the wasps under all conditions. It seems pond frogs laugh at stingers and pseudo-stingers alike.

However, the success of the male wasps in freeing themselves from the tree frogs a significant percentage of the time suggests their pseudo-stingers are indeed an important defense for some species of male wasps.

"Although male wasps are thought to mimic the morphology and behavior of stinging female wasps, we demonstrated that the genital spines of male A. gibbifrons can function to counterattack predators," the researchers write.

"The defensive roles of male genitalia as counterattack devices will be found in many wasp species, of which males have pseudo-stings in their genitalia."

The research has been published in Current Biology.