Male birds are not the only animals that woo the other sex with movement and sound. Male wolf spiders will sometimes lay down a beat for 45 minutes just to win over a female.

By flexing their appendages, shaking their abdomens, and tapping their forelegs, male wolf spiders put on quite the show. And the more elaborate the act, the better.

New research on a species of wolf spider found in North America, known as Schizocosa stridulans, has found males that drum up the most complex rhythms are also the biggest hit with the spider ladies.

It's not just the good vibrations that move them, either. Ostentatious visual signals were important factors in the female's choice, despite how obvious they might make the male look to predators.

"Exactly why females are more likely to accept males with more complex displays, however, remains an open question," write the researchers, led by University of Nebraska-Lincoln evolutionary biologist Noori Choi.

"Nonetheless, despite presumably higher costs of increased signal complexity, our data demonstrate that S. stridulans males can and will actively alter their signal complexity and that this ability may be under direct selection from females."

In the study, researchers filmed female and male wolf spiders to see how they reacted to meeting one another. The dates took place on strips of filter paper, which allowed the researchers to record the animals' delicate vibrations.

The female spider was the first to arrive, and as she waited five minutes for her suitor, she unfurled a string of silk laden with pheromones, an indication that she was open to mating.

When the male arrived, the spiders were allowed to interact for up to 20 minutes.

Across 44 mating trials, researchers found males copulated more and faster if they produced complex signals in their courtship.

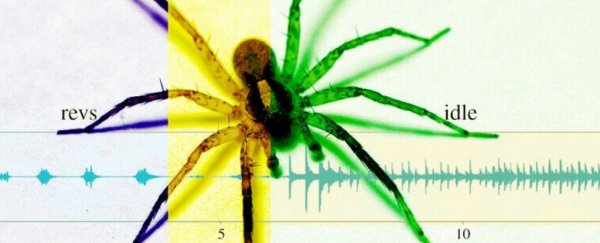

This meant mixing up the transitions between two noises, what sounds like a fingernail on a rough surface (aka 'revs') and the clattering of high heels on a linoleum floor (aka 'idles').

These signals are not only watched by the female spider, they are felt in the form of vibrations (as spiders don't have ears).

In cases where the female looked especially fertile, as conveyed by her body size, successful male spiders stepped up their transitions and began improvising with patterns of sound.

The findings suggest male wolf spiders are altering their signaling complexity according to feedback from the females.

"We see that in lots of other animal groups, but people who work on other animal groups are often surprised when they see stories of spiders engaging in these sophisticated behaviors," says behavioral ecologist Eileen Hebets from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

"We've found this now in several studies, and it really drives home the point that spiders are just as sophisticated as any other animal when you're talking about communication."

In studies on other species of wolf spiders, researchers have found males that use various types of signals are more successful at mating than those that can only employ visual or vibratory signals on their own.

The complex setlist seems to be a classic example of sexual selection, where female choice helps sculpt more and more elaborate means for sex.

The male wolf spider's taps and shakes are clearly striking a chord with females, but whether or not these signals convey something deeper is unknown.

In the study, male wolf spiders were not more successful at winning over a female if they were larger in size. But perhaps the complexity of taps and shakes is telling the female how fit the male is in some other way.

"Females aren't necessarily looking for the biggest male or the loudest male or the strongest male," says Hebets. "But maybe they're looking for a male that is really athletic and can coordinate all of these different signals into one display."

The same debate currently exists across other elaborate forms of sexual selection in the animal kingdom. Are these complex courtships a sign of high-quality mates, a sensory bias exploited by the males, or do they simply boil down to female aesthetic preference?

Perhaps the wolf spider can help us figure the mystery out.

The study was published in Biology Letters.