A Florida man in his 70s contracted an extremely rare, life-threatening infection in his implanted defibrillator after eating a feral pig in 2017.

Before cooking and consuming the gift from a local hunter, the man remembers handling the raw meat with bare hands.

Experts suspect it was at this moment that he was unknowingly exposed to a sneaky bacterium, Brucella suis.

Years later, the man began experiencing feverish symptoms, intermittent pain, excess fluid, and a hardening of the skin on the left side of his chest, according to a case study, led by infectious disease specialist Jose Rodriguez from the University of Florida.

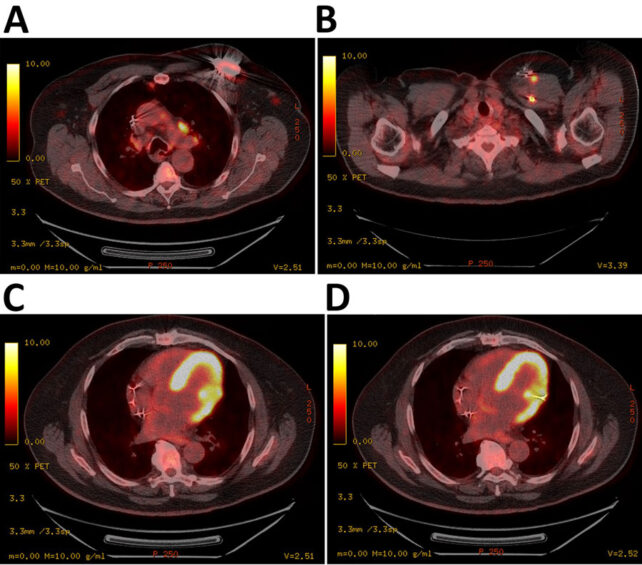

When doctors finally figured out what was going on, the insidious bacterial infection had already slipped into the man's defibrillator, passing through the chest wall, the left subclavian vein, and into the muscular tissue of his left ventricle.

The safest option was to replace the medical device completely.

Globally, brucellosis is the most common bacterial infection that spreads from animals to humans, and it is usually carried by cows, goats, sheep, and pigs.

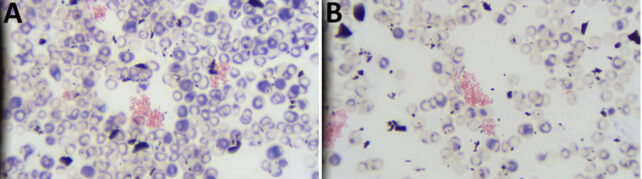

Infections of B. suis and its close relatives are tricky to treat because they can hide inside immune cells for years on end, causing only mild, feverish symptoms that come and go at random. Since the bacteria are hard to isolate and grow in the lab and easily misidentified, as occurred in this case, blood tests don't always pick them out.

Defibrillators are a perfect place for Brucella bacteria to hide. Antibiotics are difficult to deliver to these implants because of their limited blood supply, which means that if infected, taking out the whole device is often the only way to ensure proper treatment.

While severe and life-threatening, a Brucella infection of a defibrillator is extremely rare. In a 30-year review of 5,287 patients with a defibrillator, only one patient had a Brucella infection requiring complete device and lead removal with antibiotic therapy.

A series of unfortunate events led to the Florida man's diagnosis.

In the spring of 2019, long after the man had handled raw pig meat, he began experiencing uncomfortable symptoms on the left side of his chest.

The unfortunate fellow, who also suffers from type 2 diabetes and heart failure, was admitted to the hospital several times that year, where he was treated with a whole host of antibiotics.

His blood cultures revealed an infection with a different bacterium from B. suis, and an ultrasound of his heart showed his defibrillator had migrated to the left chest wall, just below the nipple.

In 2020, his symptoms persisted, so the man sought treatment once again at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

While doctors could find no outward sign of bacteria on his defibrillator's valves or leads, they were concerned by the possibility of an overlooked infection, and so they decided to take the automated implant out of his body.

Lab analysis later confirmed the device was contaminated by B. suis. The previous bacterium was a misidentification.

"Substantial delays between Brucella exposure and clinical symptoms have been previously reported in patients with cardiac implantable electronic device infections," write the authors of the case study.

"In this case, the intermittent use of antibiotics with device retainment likely led to a prolonged clinical course."

After six weeks of taking two antibiotics, the man's infection was cleared.The patient was outfitted with a new defibrillator four months after his old one was removed.

Now, more than three years later, his blood shows no clinical evidence of brucellosis. His story is a cautionary tale to all who partake in eating unpasteurized dairy products or wild animals.

In the US, feral swine (Sus scrofa) are the principal carriers of B. suis, as livestock are often vaccinated against these infections. Today, there are more than a million feral pigs living in Florida, which suggests the infection may be endemic to some parts of the nation.

The study was published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.