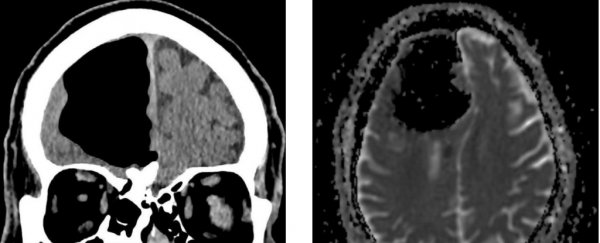

When an 84-year-old man in Ireland showed up at the doctor with complaints about being unsteady, the team found a strange reason for his new clumsiness. CT scans of the patient's brain showed a large portion of his right frontal lobe appeared to be missing.

He had been referred to the hospital due to experiencing an increased number of falls and feeling unsteady for several months; additionally, in the three days prior to his admission, he had started feeling weakness in his left side.

Because increased loss of balance and unilateral weakness presented together are often the sign of a stroke, the doctors sent the patient for a CT scan.

The result was baffling - a large black hole, nine centimetres (3.54 inches) across, where his right frontal lobe should be.

An MRI confirmed that the man's brain matter wasn't actually gone; rather, he had an air cavity inside his skull called a pneumatocoele. These are usually seen in patients with facial injuries, respiratory infections, or those who have undergone surgery for skull base tumours, the doctors wrote in a case report.

But none of these turned out to be the reason for the patient's large pneumatocoele.

The MRI also revealed the presence of an osteoma, a common type of benign bone tumour, on the man's ethmoid bone, which separates the nasal cavity from the brain.

This eroded part of the bone, which in turn allowed air to be pushed into his skull under what the doctors called a "one-way valve effect."

(Lehmer et al./BMJ Case Reports)

(Lehmer et al./BMJ Case Reports)

This can be a rare, but not unknown, complication of sinus-based osteoma.

In the end, it also turned out that the doctors' initial concerns were spot-on - because of the pressure on his brain, the patient did also have a minor stroke.

The doctors suggested "surgical management" whereby a team of neurosurgeons would get rid of the air in the patient's skull and repair the damage done, while an ear, nose and throat surgeon would remove the bone tumour.

After hearing about the risks involved with surgery, the patient flat-out refused it, and was discharged on secondary stroke prevention.

"Conservative management with observation (as in our case) has been documented in some cases, with improvement in symptoms over time, but can also lead to worsening of symptoms or ascending infection," the doctors wrote.

Thankfully, a follow-up after 12 weeks revealed that the patient remained well, and was no longer feeling weak on his left side.

The doctors have published their paper in the journal BMJ Case Reports.