A Bronze Age armor suit, one of the oldest of its kind, has finally proven itself some 3,500 years after it was forged.

The suit was discovered in 1960 after a foiled looting attempt in a richly furnished tomb for a fallen warrior, excavated at an archeological site near the village of Dendra in southern Greece.

Thought to be one of the oldest complete armored suits of the European Bronze Age, the Dendra panoply, as it came to be known, has puzzled archeologists in the 60-odd years since it was found.

Wholly intact, it looked solid but early experiments with replicas suggested it wasn't suited for use in long battles. So was the suit purely ceremonial or only for those who rode to battle in chariots, archaeologists wondered?

Not so, according to a new study from researchers who had a group of 13 marines from the Hellenic Armed Forces test the suit in an 11-hour-long simulation of battle conditions recreated from historical texts. They found the Dendra suit would have been "entirely compatible with use in combat" and the demands of war.

Historical reenactors will go mad for the researchers' efforts. They extracted information about warfare and battle tactics in ancient Greece from a well-accepted translation of the Iliad, a lengthy poem about the final throes of the Trojan War, which took place around 1300 to 1200 BCE.

"As no historical accounts or descriptions survive from the Greek Late Bronze Age regarding the scope and use of armor of the Dendra type, we turned to a key – and only – detailed early account of warfare, battle, and single combat: Homer's epic account of 10 days in the Trojan War, the Iliad," the researchers explain in their published paper.

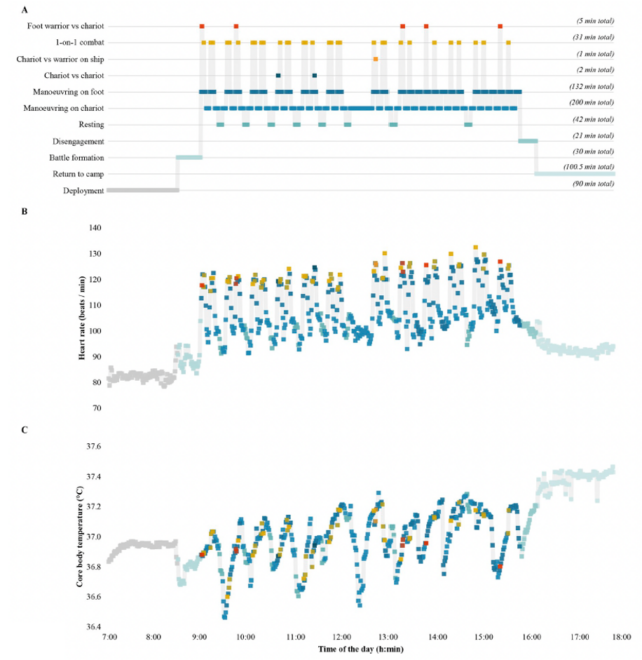

The team analyzed the text and reviewed other literature, looking for details of battlefield environments, how long daily battles in the Trojan War typically lasted, what warriors ate and drank, and the types of maneuvers, combat techniques, and weapons typically used.

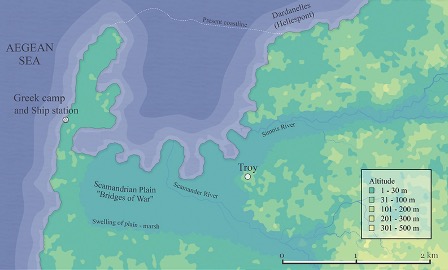

They combined this with published sedimentology and geomorphology data that situates the final battles of the Trojan War in a low-lying 4 square-kilometer (1.5 square miles) area of swampy plains near the Scamander River, which encircled the city of Troy.

They estimated warriors in the latter stages of the Trojan War would have fought in June temperatures of 24–29 °C (75–84 °F) and sweated in the relative humidity of 70–85 percent. Daily army operations probably lasted 11 hours after a typical breakfast of dry bread, goat's cheese, olives, and red wine.

From accounts of Trojan battles, the team also established that warring sides constantly attacked, retreated, recovered, gained ground, and retreated – fighting activity that resembles what we might today call high-intensity interval exercise.

All this, to "create a combat simulation protocol replicating the daily activities performed by elite warriors in the Late Bronze Age," write exercise physiologist Andreas Flouris of the University of Thessaly in Greece and colleagues.

Ultimately, thanks to the marines' grueling efforts in replica Dendra suits, the team found that the armor would not have limited a warrior's fighting ability or caused severe strain on the wearer.

Although they acknowledge that the Iliad may not provide an accurate representation of the fighting tactics of Greek Mycenaean warriors, it's "undoubtedly" the best account we have to work with.

"Our results support the notion that the Mycenaeans had such a powerful impact in Eastern Mediterranean at least partly as a result of their armor technology," Flouris and colleagues conclude.

"This may also help shed much-needed light on one of history's most frightful turning points: the collapse of the Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age civilisations towards the end of the 2nd Millennium BCE; a time of destruction and upheaval that marked the beginning of the Age of Iron."

The study has been published in PLOS ONE.