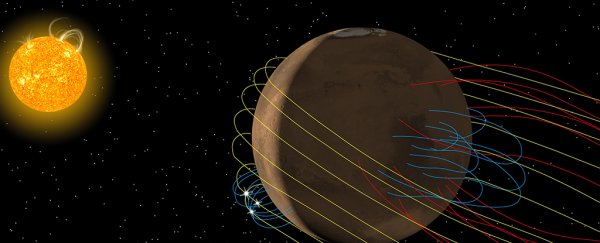

NASA has found an invisible, twisted magnetic tail trailing behind Mars as it orbits the Sun, caused by the effects of rushing solar winds, and perhaps explaining more about how the Martian atmosphere escapes into space.

This unique insight was revealed by readings from the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission (MAVEN) spacecraft, which showed how the Red Planet's local magnetic fields behave differently from the global magnetic field around Earth.

Interactions between magnetic fields in the Sun's solar winds, and the pockets of magnetism left on Mars, could give remaining atmospheric particles an escape route out into space, according to scientists at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

"We found that Mars' magnetic tail, or magnetotail, is unique in the Solar System," says one of the team, Gina DiBraccio.

"It's not like the magnetotail found at Venus, a planet with no magnetic field of its own, nor is it like Earth's, which is surrounded by its own internally generated magnetic field. Instead, it is a hybrid between the two."

The solar winds, made up of electrically conducting gas blown out by the Sun, are thought to have stripped away much of the Martian atmosphere billions of years ago.

Now, those same winds are causing the unique magnetotail effect as their combine with the leftover regions of magnetism still present on certain parts of Mars.

The solar winds carry their own magnetic fields, and if they hit a region on Mars oriented in the opposite direction, it causes an effect called magnetic reconnection. It's here that the invisible twist happens.

"Our model predicted that magnetic reconnection will cause the Martian magnetotail to twist 45 degrees from what's expected based on the direction of the magnetic field carried by the solar wind," says DiBraccio.

"When we compared those predictions to MAVEN data on the directions of the Martian and solar wind magnetic fields, they were in very good agreement."

That magnetic reconnection could also be pushing more of the already thin atmosphere on Mars out into space, as electrically charged ions in the planet's upper atmosphere respond to the magnetic field created by the tail.

The magnetotail essentially gives these particles a path to follow to flow off the planet, using energy created by the magnetic reconnection – like a stretched rubber band suddenly snapping back into place, according to NASA.

Because MAVEN is continually changing its orbit in relation to the Sun, it's been able to map the magnetic fields of Mars in their entirety, and build up a map of the way the magnetotail is sent twisting and fluctuating by the solar winds.

Next, the researchers want to examine readings from instruments on MAVEN besides the magnetometer to confirm that reconnected magnetic fields are indeed contributing to atmospheric loss, and to what extent.

All of which is going to be vital information if we decide to settle down on the Red Planet in the next few decades – that lack of atmosphere is one of the main stumbling blocks.

"Mars is really complicated but really interesting at the same time," says DiBraccio.

The research has been presented at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences in Utah.