The beautiful gullies we see on Mars today probably aren't being formed by flowing water, NASA has announced.

Until now, liquid water was one of the leading candidates thought to be carving out the distinctive channels along the Red Planet's surface, but researchers say the latest data rules out that possibility.

It's important to note that these gullies are distinctive from the 'recurring slope lineae' (or RSL) that were discovered on the surface of Mars last year.

RSL look like dark streaks, and they form during the warmer months and fade away in winter. Scientists have found strong evidence - in the form of hydrated salt - that those are caused by flowing water.

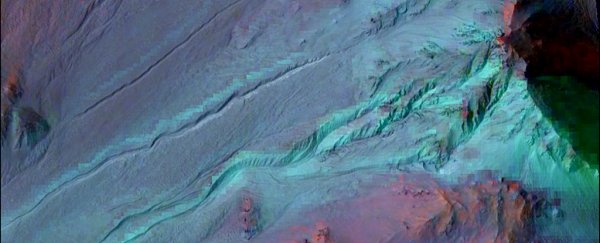

Gullies, on the other hand, occur between 30 and 50 degrees latitude in both the northern and southern hemispheres, and are more of a deep 'channel-like' structure.

They were first discovered back in 2000, getting everyone excited about the presence of liquid water on Mars, because they looked a lot like gullies here on Earth - which we know are formed by liquid.

But, back in 2014, NASA found evidence that these gullies were more likely formed by the seasonal freezing of carbon dioxide, not liquid water after all, and it was unlikely that there would be enough water on the surface of the Red Planet to carve something like them out.

Still, scientists have remained divided on the issue, and seeing as no rovers have gotten close enough to analyse the minerals present at the sites, we haven't had any definitive evidence either way.

But new data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) adds further weight to the hypothesis that these channels weren't carved out by water, as much as we all love the idea of rivers flowing across the Red Planet.

To figure this out, researchers from Johns Hopkins University examined high-resolution data on more than 100 gully sites across Mars.

That data came from the MRO's on-board spectrometer, known as CRISM, which is able to perform chemical analyses by measuring the wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation being emitted by a sample.

They were looking for any trace of water or its by-products near the gully, but failed to find any - making it very unlikely that water played a role in making them.

"The findings showed no mineralogical evidence for abundant liquid water or its by-products, thus pointing to mechanisms other than the flow of water - such as the freeze and thaw of carbon dioxide frost - as being the major drivers of recent gully evolution," the team explains in a press release.

But that doesn't mean water was never involved, simply that it hasn't been involved in recent history.

"On Earth and on Mars, we know that the presence of phyllosilicates - clays - or other hydrated minerals indicates formation in liquid water," said study leader Jorge Núñez.

"In our study, we found no evidence for clays or other hydrated minerals in most of the gullies we studied, and when we did see them, they were erosional debris from ancient rocks, exposed and transported downslope, rather than altered in more recent flowing water."

"These gullies are carving into the terrain and exposing clays that likely formed billions of years ago when liquid water was more stable on the Martian surface," he added.

So, we still can't say for sure what formed these gullies, but we've now ruled out one hypothesis. And hopefully as we get more data we'll have a better idea of the current geological processes shaping the surface of Mars… especially seeing as we hope to live there one day.

The research has been published in Geophysical Research Letters.