Belief in witchcraft is widespread around the world, according to a new global study that involved more than 140,000 people – but it's highly variable from place to place.

Based on the results, about a billion people across 95 countries believe in witchcraft, and the study notes that is "most certainly an undercount", given the sensitivity of discussing witchcraft for some respondents.

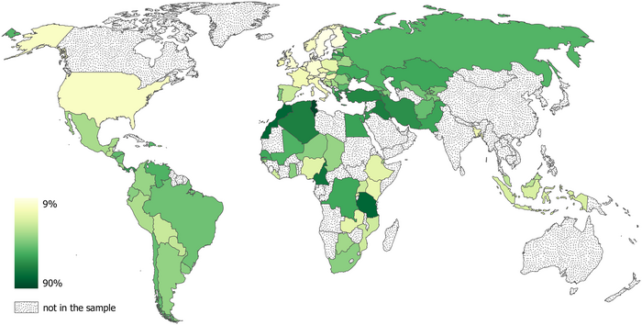

While at least some people believe in some version of witchcraft almost everywhere – about 40 percent of those who took the survey said they do – the local prevalence of those beliefs seems to vary widely.

In Sweden, for example, only 9 percent of participants reported a belief in witchcraft, according to the study, compared with 90 percent in Tunisia.

Although witchcraft beliefs are more common in some countries than in others, they still "cut across socio-demographic groups" in each country, writes study author and economist Boris Gershman from American University.

Earlier research examined witchcraft beliefs in various parts of the world, but a dearth of data has prevented researchers from conducting global analyses of witchcraft beliefs.

Gershman built a new dataset from in-person and telephone surveys conducted between 2008 and 2017 by the Pew Research Center and other professional survey groups.

The surveys included questions about respondents' broader religious beliefs and belief in witchcraft.

Gershman notes that pollsters asked about magic and witchcraft in many different ways, but at least one relevant question appeared in every survey.

All the surveys asked respondents if they believe in the "evil eye," or the idea that "certain people can cast curses or spells that cause bad things to happen to someone," Gershman writes in the new study.

The latter part of the question captures the definition of witchcraft Gershman is going for, and thanks to its prevalence in these surveys, it "provides a unique way to pinpoint witchcraft believers in the entire merged survey sample," he writes.

Gershman found that 40 percent of respondents globally said they believe in this description of witchcraft.

Applied to the total populations of the countries represented, that would translate to about 1 billion people, he writes.

This new dataset also lets Gershman look at the links between witchcraft belief and a variety of individual-level and country-level factors.

At the individual level, people with more education and economic security were less likely to believe in witchcraft, the study found.

Witchcraft beliefs also correlated positively with religiosity and a belief in a deity, but affiliation with Christianity or Islam didn't make a significant difference.

At the national level, witchcraft beliefs are associated with weak institutions, low levels of social trust, and low innovation, Gershman reports, as well as with conformist culture and higher levels of in-group bias.

"The study documents that witchcraft beliefs are still widespread around the world," he says.

"Moreover, their prevalence is systematically related to a number of cultural, institutional, psychological, and socioeconomic characteristics."

Gershman acknowledges that more research is still needed to gain a truly global perspective on witchcraft beliefs. Despite its broad scope, the new study has some limitations, such as its lack of data from China and India, the planet's two most populous countries.

There are practical applications for studying witchcraft beliefs in such detail, Gershman adds. For one thing, these beliefs still lead to conflict in some places, and a better understanding of those beliefs – and their social context – may help protect women accused of witchcraft.

Understanding witchcraft beliefs can also be critical for governments, researchers, or aid groups trying to help or work with local populations.

Gershman quotes in his study the late anthropologist Monica Hunter Wilson, who eloquently explained the need for research like this:

"I see witch beliefs as the standardized nightmare of a group," Wilson said, "and I believe that the comparative analysis of such nightmares is not merely an antiquarian exercise but one of the keys to the understanding of society."

The study was published in PLOS One.