In January 1912, German geophysicist Alfred Wegener proposed an idea the scientific world thought was wack.

After scrutinizing similar-looking fossils of plants and animals on different land masses, he wondered if perhaps the continents had once been joined together before somehow separating into a new configuration.

His work was roundly scorned, and dismissed as "delirious ravings". Now, of course, the idea of continental drift is accepted as established science, with many different lines of evidence all pointing in the direction of Wegener's supercontinent, now known as Pangea.

Paleontologists have just identified another example that would have delighted the geophysicist; almost identical sets of dinosaur footprints have been found in Cameroon in Central Africa and in Brazil in South America, separated by a distance of more than 6,000 kilometers (about 3,700 miles).

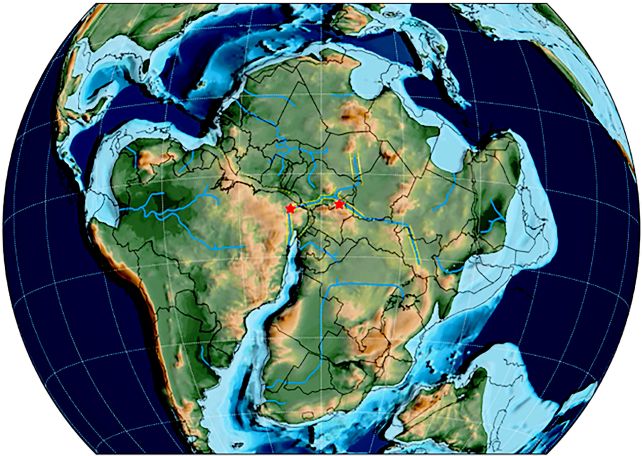

These two locations define one of the last places dinosaurs could cross between the land masses freely before the continent of Gondwana – a fragment of Pangea – broke away completely, some 120 million years ago.

Together, there are more than 260 footprints, stamped into the mud of riverbanks by ornithopod, sauropod, and theropod dinosaurs across what might have been the last land bridge connecting Africa to South America.

"We determined that in terms of age, these footprints were similar," says paleontologist Louis Jacobs of Southern Methodist University. "In their geological and plate tectonic contexts, they were also similar. In terms of their shapes, they are almost identical."

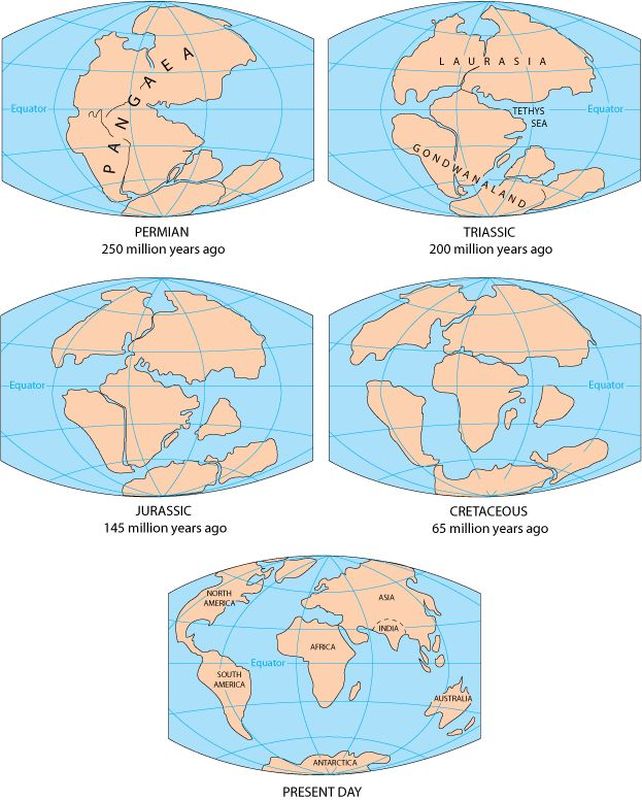

The metamorphosis of Earth's continental configuration was not a one-and-done event, but a long, ongoing process that continues to this day, with the continents continuing to slowly move around the globe.

We can piece together past arrangements by looking at features such as the shapes of and alignments of shorelines, matching mountain ranges and rock types that are similar across continents, and even fossils that are similar to each other as Jacobs and his team have done here.

From lines of evidence such as these, scientists have determined that Africa and South America started to split apart from each other around 140 million years ago. Rifts formed in the crust, and a gap between the two pieces of Gondwana started to widen. In these cracks, magma flowed up from below, hardening into a new crust that would form the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. As the two new continents continued to separate, the points at which animals could move between them became smaller and fewer.

"One of the youngest and narrowest geological connections between Africa and South America was the elbow of northeastern Brazil nestled against what is now the coast of Cameroon along the Gulf of Guinea," Jacobs explains. "The two continents were continuous along that narrow stretch, so that animals on either side of that connection could potentially move across it."

To find those points of passage, he and his colleagues made a careful study of the published literature. They reconstructed the sundering of the continents, making the case for a connection point between Borborema in Brazil and Cameroon. Then, they studied the dinosaur tracks in both regions, comparing them, and finding that they matched.

Because of this connection, we can extrapolate that other, perhaps less heavy-footed animals could follow similar paths.

This, the team says, means that the two places formed what they have named the Borborema-Cameroon dinosaur dispersal corridor – one of the very last places animals could move between the continents before they split apart completely.

"This study places dinosaur tracks in a context to elucidate an appropriate path of biogeographical exchange between what would soon (geologically) become separate continents," the researchers write in their paper.

"We have tracked dinosaur footprints from the time they were impressed in mud along rivers and lakes over 120 million years ago, in localities originally contiguous and on a single landmass but some 1000 kilometers apart. Today, these sites of fossil preservation are on two continents separated by 6000 kilometers and an ocean."

The paper, titled "The Early Cretaceous Borborema-Cameroon Dinosaur Dispersal Corridor", has been published in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, as a tribute to late paleontologist Martin Lockley, who was an avid scholar of dinosaur tracks. This paper will not be made available online.