Anthropologists have peered through the thick jungle of Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula and identified a long-lost Maya city with stepped temple pyramids to rival Chichén Itzá, Río Bec, and Tikal.

Fieldwork on the ground is yet to be conducted by archaeologists, but based on remote sensing data, which maps entire landscapes under dense forests in minute detail, it seems this lush and verdant forest was once home to the Maya.

The newly described city, named Valeriana, features a crowded urban landscape and rural fringes that surpass any known Maya cities found in Belize or Guatemala.

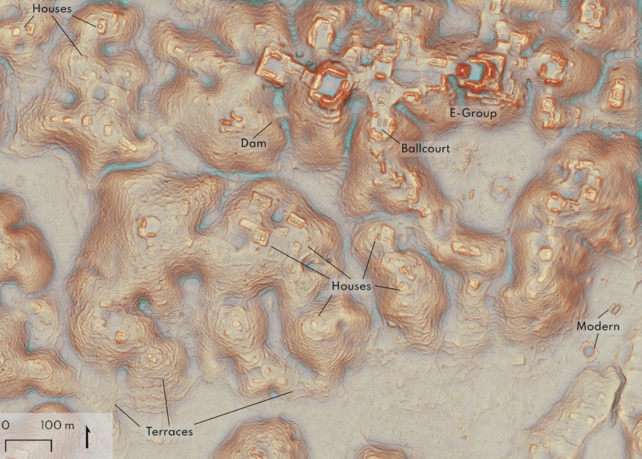

Researchers from the US and Mexico have tallied no less than 6,764 structures hiding beneath the canopy that have never been studied before.

Since the 1940s, scientists have known parts of the Yucatán Peninsula, including the modern states of Campeche and Quintana Roo, were once densely settled and extensively engineered by the Maya between 250 and 900 CE.

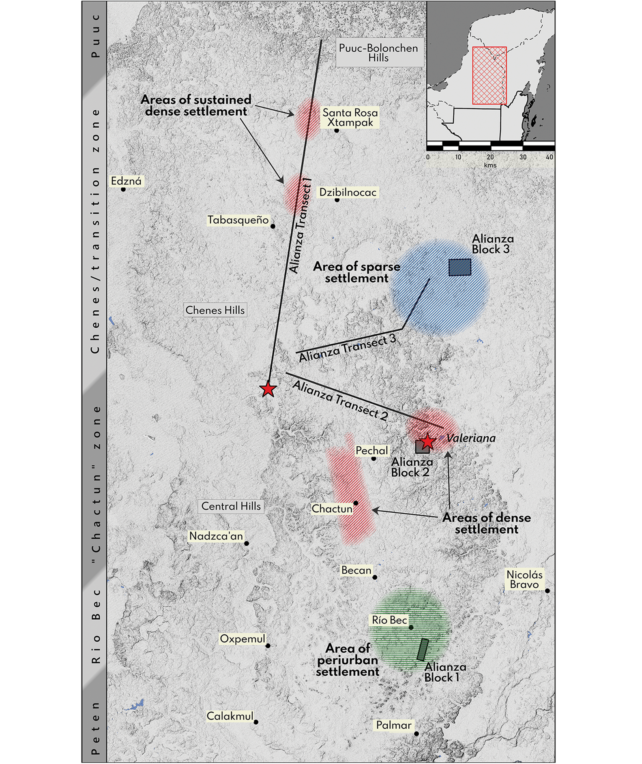

Compared to other regions of the peninsula, however, the eastern jungles of Campeche and the western fringes of Quintana Roo were "essentially terra incognita" within the authoritative database, scientists say.

Locals, meanwhile, have long known there are ruins here.

"We didn't just find rural areas and smaller settlements," says Luke Auld-Thomas from Tulane University and Northern Arizona University in the US.

"We also found a large city with pyramids right next to the area's only highway, near a town where people have been actively farming among the ruins for years.

"The government never knew about it; the scientific community never knew about it. That really puts an exclamation point behind the statement that, no, we have not found everything, and yes, there's a lot more to be discovered."

The first block of Maya ruins mapped by Auld-Thomas and his colleagues was found just south and east of Río Bec – a famous pre-Columbian Maya site with temple pyramids built in a unique architectural style.

The new site has two paired pyramids, and the pattern of its ruins is similar to the 'dense rural' agricultural settlement of Río Bec.

The second block of Maya ruins seems to be the epicenter of a major urban area. The city of Valeriana includes a freshwater lagoon, and two major hubs of monumental architecture linked via a dense settlement.

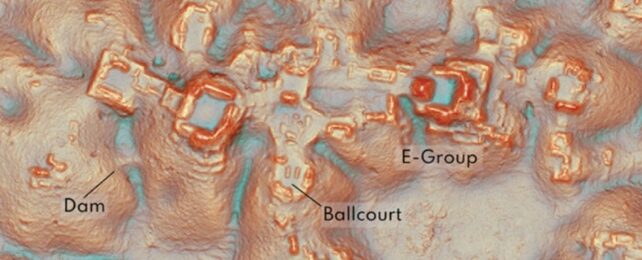

One of these hubs has "all the hallmarks of a Classic Maya political capital", anthropologists explain, including temple pyramids, a ballcourt, a seasonal watercourse, multiple enclosed plazas, and a causeway connecting them.

Altogether, the infrastructure covers every inch of the survey area, about 16.6 kilometers (6.4 miles) squared. Field walls and terraces for farming are ubiquitous.

"The discovery of Valeriana highlights the fact that there are still major gaps in our knowledge of the existence or absence of large sites within as-yet unmapped areas of the Maya Lowlands," the team writes.

The third and final block is quite different. It is sparse and has only scattered or loosely clustered residences, with no monuments or water storage facilities that can be seen using Lidar.

Some experts, however, argue that Lidar tech is making the Yucatán look more densely settled than it actually was. Today, there exists much debate around whether large Maya sites were actually cities, hosting large populations, or just places for the elite to hang out and feel special.

Based on this new find, however, Auld-Thomas and his colleagues say they "can only conclude that cities and dense settlements are simply ubiquitous across large swaths of the central Maya Lowlands."

"Anyone who is waiting for a sparsely settled Maya hinterland… is running out of places to look," they add.

The study was published in Antiquity.