Wombats are among the most peculiar of animals. They look like a massively overgrown guinea pig with a boofy head, a waddling gait, squared-off butt, backwards-facing pouch and ever-growing molars.

Indeed, wombats are oddballs and don't look much like their nearest living relatives, the koala. But koalas and wombats (collectively known as "vombatiformes") are the last survivors of a once far more diverse group of marsupials whose fossil history stretches back for at least 25 million years.

Working out how this diverse group fizzled out to just wombats and koalas has taken centuries of extraordinary discoveries in the fossil record. We are announcing one of these today in our research published in Scientific Reports.

Mukupirna nambensis is one of the oldest discovered Australian marsupials. Its unveiling has deepened our understanding of the relationships and evolutionary history of one of the strangest groups that once ruled this continent.

The common wombat (Vombatus ursinus). (JJ Harrison/Wikipedia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The common wombat (Vombatus ursinus). (JJ Harrison/Wikipedia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Acupuncturing the earth

In 1973 at Lake Pinpa – a small dry salt lake in South Australia – a multi-institutional expedition led by palaeontologist Dick Tedford from the American Museum of Natural History discovered a host of extinct animals.

A combination of drought and strong winds had blown the sand off the surface of the lake bed, revealing the remains of animals that died after getting stuck in mud 25 million years ago.

One of the discoveries was a skull and partial skeleton of a large, distinctive wombat-like animal that was clearly new to science – Mukupirna.

Its fossils were found by pushing a metal rod into the clay at intervals across the lake surface, a bit like acupuncturing the skin of Mother Earth. If the rod struck something hard, the team excavated down to find what was commonly the fossilised skeleton of an otherwise unseen animal.

Once uncovered, they were encased in plaster shells for transport back to the Museum of Natural History, where they were subjected to years of careful preparation. Although Mukupirna was discovered this way in 1973, it's only now we can formally announce this discovery to the world.

A mammoth find

One of the most remarkable things about this marsupial is its large size, which we estimate was between 143-171 kilograms (315 to 377 pounds), more than four times larger than any living wombat.

Its size inspired the scientific name Mukupirna, from the words muku, meaning "bones" and pirna, meaning "big", in the Malyangapa and Dieri languages of Aboriginal people from central Australia.

We worked out the earliest vombatiform marsupials probably weighed about 5 kilograms (11 pounds) or less (about the size of a modern koala). That said, body weights of about 100 kilograms, such as that of Mukupirna, then evolved independently at least six times in different branches of the family tree.

The biggest of these would be Diprotodon at about three tonnes, the world's largest marsupial.

Giant wombat relative [Mukupirna nambensis] skull. (Julien Louys/Griffith University/Robin Beck/University of Salford)

Giant wombat relative [Mukupirna nambensis] skull. (Julien Louys/Griffith University/Robin Beck/University of Salford)

Behaviour up to scratch

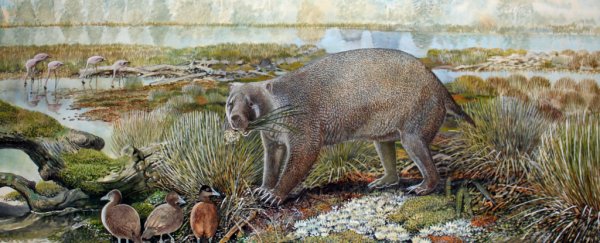

Mukupirna's forearms were powerfully muscled and its hands may have worked like shovels, an attribute shared with modern wombats. Also like wombats, it was probably a good scratch-digger. But unlike today's wombats, it probably couldn't burrow.

Although Mukupirna was clearly herbivorous, unlike wombats its cheek teeth were low-crowned with well-developed roots. This indicates it couldn't have survived on abrasive plant materials such as grasses, which today's wombats consume without problems.

Pollens in the fossil deposit indicate that, unlike today, there were no grasslands in this area of central Australia back then. Instead, it was dominated by scrubby rainforest that was also home to possums, koalas and galloping kangaroos.

But alongside them were much stranger, more primitive animals that have left no living descendants. These included Ilaria, which was a bit like a gigantic koala, Ektopodon, an arboreal marsupial with teeth like a cheese-grater and Wakaleo, a leopard-sized marsupial lion with some of the most ferocious butchering teeth ever evolved by a mammal.

These forests were also punctuated by huge inland lakes that were home to lungfish, turtles, crocodiles, flamingos, ducks, stone curlews and even freshwater dolphins.

A lost land

By comparing different features of Mukupirna's teeth and skeleton, we discovered it to be the closest known relative of modern wombats. Yet, it was as different from wombats as wombats are from koalas, which is why it has been placed in a new family of its own: the Mukupirnidae.

Formal recognition of Mukupirna fills yet another fascinating gap in our knowledge of the weird and wonderful evolutionary history of mammals on this continent.

Sadly, it's likely all mukupirnids vanished when a shift in global climate triggered an environmental change from scrubby rainforests 25 million years ago, to far lusher and more biodiverse rainforests 23 million years ago.

This would have resulted in more intense greenhouse conditions and an environment presumably not suited to mukupirnids.

Hopefully this rings a warning bell about the state of Earth's climate now. If we can't slow the global heating we've triggered, how many more of Australia's uniquely endemic living creatures will soon join Mukupirna in the increasingly crowded abyss of extinction? ![]()

Robin Beck, Lecturer in Biology, University of Salford; Julien Louys, ARC Future Fellow, Griffith University; Mike Archer, Professor, Pangea Research Centre, UNSW, and Philippa Brewer, Senior Curator, Natural History Museum.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.