Life was put to the ultimate test a quarter-billion years ago as extinction events ravaged Earth's biosphere, leaving a mere handful of species to claw their way back to survival.

This 'Great Dying' appears to have been driven by a complex series of incidents, with a new study finding prolonged, intense climate fluctuations not unlike modern El Niños almost undoubtedly made a bad situation a lot worse.

Using proxies to gauge fluctuations in seawater temperatures, and updated climate modeling, an international team led by China University of Geosciences geologist Yadong Sun developed simulations for the ebb and flow of oceanic and atmospheric currents some 250 million years ago.

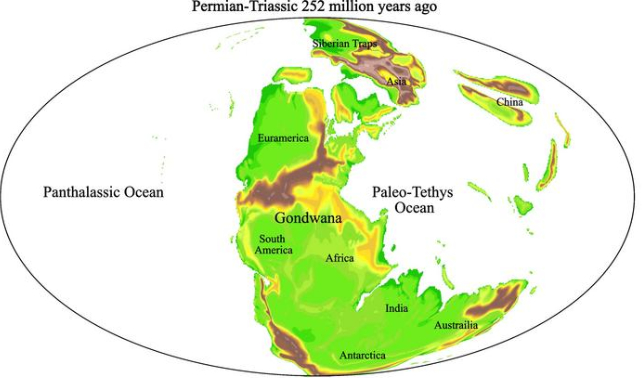

Life diversified in the eons leading up to the catastrophic extinctions that saw the Permian give way to the first age of the dinosaurs, the Triassic. A single global ocean surrounded an amalgamation of the continents, creating a dry interior edged by cool coastal waters.

Conifers thickened into forests as the four-legged ancestors of modern mammals, birds, and reptiles scurried beneath their branches.

Things were fine, until they weren't. Of those burgeoning families of tetrapods, as few as 10 percent would go on to found future generations. Millions of years later, ocean species began to vanish one by one, until a mere one in five remained.

Never has the world since seen the likes of such a loss of life, prompting researchers to ask why this particular period was so toxic.

An immense layer of igneous rock in what is now Siberia points to an extensive period of volcanic activity spanning the Permian-Triassic boundary 252 million years ago that is too coincidental to ignore.

Piecing together other bits of evidence, the team suspects a variety of knock-on effects from constant eruptions stripping ozone and dumping more than enough carbon dioxide to warm the atmosphere, while microbial blooms flooded the oceans with oxygen before sucking it back out again.

As cataclysmic as this sounds, the biosphere has faced this kind of devastation without coming close to such losses. Many of the more robust species adapt to otherwise inhospitable shifts in conditions, by moving towards the poles for instance, or finding new sources of shelter and water.

What hasn't been considered previously is the impact of large, short-term fluctuations in temperature and precipitation. Even today, wild swings in weather driving floods and droughts, and heat waves and cold snaps, are responsible for widespread ecological losses.

Analyzing ratios of oxygen isotopes in the fossilized teeth of ancient marine life, the researchers estimated a timeline of temperature changes that implied some serious weakening of atmospheric air currents when considering broader climate systems.

Today, similar zonal shifts in sea surface temperatures engage in a feedback cycle with what's known as the Walker circulation. Without its usual strength, this rotation of air relents, changing the distribution of surface waters across the Pacific to send warm, moist air east to South America and desiccated air west to dry out Australia and Indonesia.

These El Niño events are problematic to say the least, despite persisting for just a year or two. Comparable changes at the end of the Permian could have seen 'mega' El Niño periods that didn't just last longer, but were far more intense.

Confronted with the highs and lows of droughts and floods as well as heat and milder conditions, species that may have tolerated intense climate shifts could have instead struggled to adapt, compounding the rate of extinctions.

Though the models imply climate oscillations, the researchers would need to uncover more direct evidence of fluctuation conditions in the geological record to be truly confident they were onto something.

The findings could put our modern climate crisis into a new light, however, with predictions of modern El Niño events becoming stronger and more frequent, potentially impacting a variety of ecosystems around the globe.

Life eventually bloomed again after the Great Dying. Still, if the climate record is anything to go by, it is a stark reminder that all species have their limits.

This research was published in Science.