A landslide and its resulting megatsunami in a Greenland fjord in September 2023 were significant enough to send waves around the channel of water for an entire week, newly analyzed data collected from seismic monitors has shown.

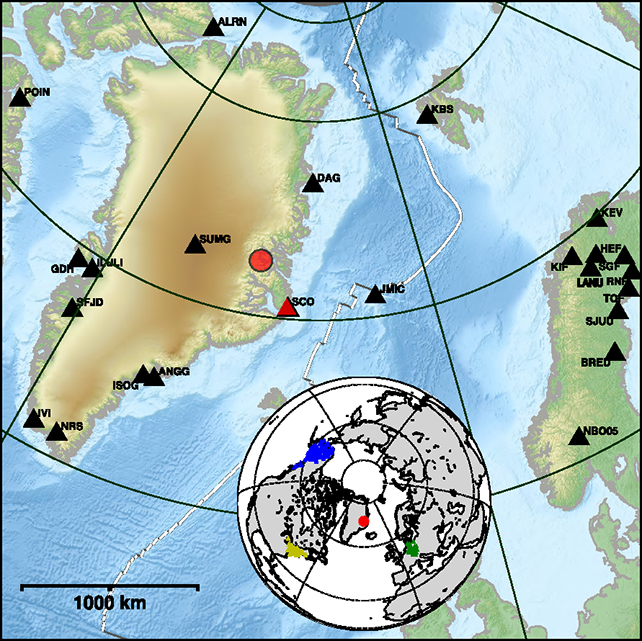

In what's known as a seiche, a number of smaller oscillations bouncing between shores combined to form standing waves in the partially enclosed body of water. The phenomenon was logged from signals that traveled as far as 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles) around the globe.

The team behind the new research, from the GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences and the University of Potsdam in Germany, says this kind of sensing technology is an important part of monitoring remote areas such as Greenland.

"The fact that the signal of a rockslide-triggered sloshing wave in a remote area of Greenland can be observed worldwide and for over a week is exciting, and as seismologists this signal was what mostly caught our attention," says geophysicist Angela Carrillo-Ponce from the GFZ German Research Center for Geoscience.

Using data obtained from satellites and seismic activity stations – measuring shock waves as they reverberate around Earth – the researchers were able to identify both a high-energy landslide that triggered the megatsunami in the Dickson Fjord, as well as the subsequent seiche that lasted for days.

According to the researchers the tsunami reached some 200 meters (656 feet) above the shore in certain places, sending water as far away as the offshore island of Ella more than 50 kilometers (31 miles) from the site of the landslide.

The evidence of the standing wave came through what's known as a very long period (VLP) signal, which recorded the ongoing impact of the landslide. There were also reports on social media of the after-effects of the event. It's not clear what caused the initial landslide, but we've got a very good idea of what happened next.

From the Artic Command Facebook page today;

— Orla Joelsen (@OJoelsen) September 21, 2023

“TSUNAMI IN DICKSON FJORD

Arctic Command was contacted on 17 September by a person on board the cruise ship OCEAN ALBATROS. The person was previously employed by SIRIUS, and he was therefore able to ascertain quite quickly that… pic.twitter.com/QTFuNk9qgI

"The analysis of the seismic signal can give us some answers regarding the processes involved and may even lead to improved monitoring of similar events in the future," says Carrillo-Ponce.

"If we had not studied this event seismically, then we would not have known about the seiche produced in the fjord system."

As the world warms, detailed monitoring of regions such as Greenland will be increasingly vital – higher temperatures mean less stability and greater variation in glaciers, and potentially landslides such as the one recorded here.

Even in a remote part of the world such as Greenland, these incidents and subsequent megatsunamis can lead to loss of life, and the hope is that improving technology will give us a better idea of where events like this might happen next.

"It is quite impressive to see that we could use good-quality data from stations located as far as Germany, Alaska and North America, and that those records were strong enough for at least one week," says Carrillo-Ponce.

The research has been published in The Seismic Record.