The latest drugs for Alzheimer's disease may add years of independence to the lives of patients, but possibly only for some. A new analysis of clinical data suggests female brains may not respond to some of these novel medications as well as male brains.

In an 18-month-long phase 3 clinical trial, the intravenous drug lecanemab slowed cognitive decline by as much as 27 percent compared to a placebo.

The findings were promising enough that the FDA approved the drug as an Alzheimer's treatment in 2023. But the difference in drug effect between the sexes was no less than 31 percent.

The trial's sample size was not large enough to compare male and female subgroups directly, but the sizable gap in preliminary results is a red flag to some scientists.

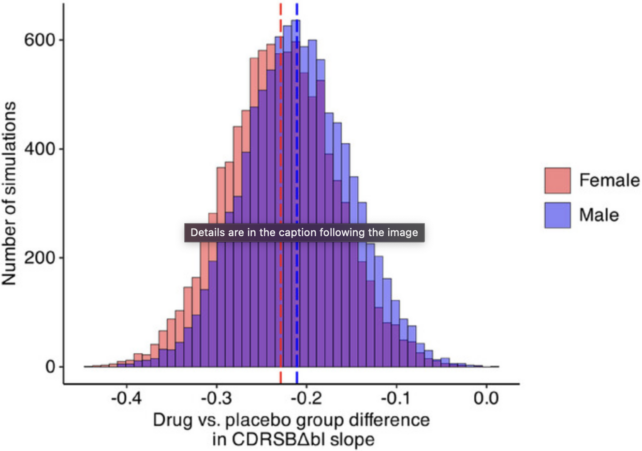

To find out more, researchers in Canada and Italy ran 10,000 simulated trials based on data from the phase 3 clinical trial, called CLARITY AD.

The results showed the difference between sexes only occurred randomly in 12 out of 10,000 simulations. What's more, known differences in brain aging between males and females could only account for a fraction of the observed 31 percent gap in drug effect.

The authors of the study, led by neuroscientist Daniel Andrews from McGill University in Canada, cannot conclude that lecanemab is clinically ineffective in females, but their results suggest the drug "has either no or limited effectiveness in females."

Further research is needed to confirm if that really is the case, but given that two-thirds of Alzheimer's patients are female, these results temper some of the recent enthusiasm around lecanemab.

The CLARITY AD trial provided its subgroup data in a forest plot, which is a visual representation only.

In that plot, males taking lecanemab showed a 43 percent mean slowing of cognitive decline, which is statistically significant. Females, meanwhile, had a non-significant 12 percent mean slowing on the drug.

The results prompted criticism from some neuroscientists, because the subgroups cannot be directly compared with any statistical strength.

"Until relatively recently, recruitment for clinical trials did not give due consideration to the possible impact of sex on outcomes and reports often did not stratify findings by sex," explained neuroscientist Marina Lynch from Ireland's Trinity College in a review of Alzheimer's drugs from 2024.

"Current knowledge strongly supports the view that trials should make assessing sex-related difference in responses a priority… "

Andrews and his colleagues agree. They argue future work should "examine possible links between a drug's action mechanism and sex differences in amyloid clearing and clinical efficacy."

Lecanemab targets amyloid protein plaques in the brain that are associated with Alzheimer's disease. But scientists are still trying to figure out how exactly the medicine works at slowing cognitive decline.

For more than three decades, amyloid plaques have been a leading culprit in the cause of dementia, and yet recent studies suggest these markers may not always be an early trigger of the disease. Even when the plaques are removed, there can still be cognitive decline.

Perhaps that is why drug treatments that target these plaques have mostly proved unsuccessful in human patients.

Lecanemab is one of a few medicines that actually works. But maybe that depends on the patient and their subtype of Alzheimer's disease.

Recent evidence, for instance, has shown that up to a third of patients with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's have no amyloid plaques in their brain in postmortem biopsies.

To add even more complexity to the matter, there is a chance that sex hormones and sex chromosomes may also play a crucial role in how these amyloid plaques form and are cleared from the brain.

This means "certain types of amyloid-targeting drugs might function differently in females and males," explain the authors of the recent review. "Research into possible mechanisms could be accelerated by drug developers sharing recent AD trial data."

The risk of Alzheimer's disease and other cognitive ailments differs significantly between the sexes, and yet in 2019, only 5 percent of published neuroscience or psychiatry studies examined the influence of sex.

Recently, an international team of psychiatrists, psychologists, and neuroscientists warned that the extreme male bias in brain aging research has "grave consequences" for wellbeing and places a "disproportionate burden" on female health.

The longer we ignore these potential sex differences, the longer it will take us to understand why female brains age differently and what we can do about it.

The study was published in Alzheimer's & Dementia.