The risk of developing Parkinson's disease is twice as high in men as in women, and new research points to a potential reason why: a normally benign protein in the brain.

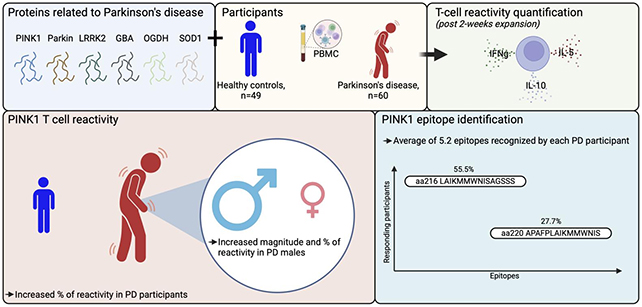

PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) protein is not normally a threat, and is important in regulating cellular energy use in the brain. However, the new research shows that in some Parkinson's cases, the immune system mistakes PINK1 for an enemy, attacking brain cells that express the protein.

According to the study, led by a team from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California, the PINK1-related damage done by the immune system's T cells is much more widespread and aggressive in the brains of men than women.

"The sex-based differences in T cell responses were very, very striking," says immunologist Alessandro Sette, from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. "This immune response may be a component of why we see a sex difference in Parkinson's disease."

Using blood samples from Parkinson's patients, the researchers tested the response of the T cells in the blood against a variety of proteins previously linked to Parkinson's – finding that PINK1 stood out.

In the male Parkinson's patients, the research team noticed a six-fold increase in T cells targeting PINK1-tagged brain cells, compared with healthy brains. In the female Parkinson's patients, there was only a 0.7-fold increase.

Some of the same researchers had previously found something similar happening with T cells and the alpha-synuclein protein. However, these reactions weren't common to all Parkinson's brains, which prompted the hunt for more antigens – substances that trigger immune responses.

As is always the case with research of this type, once experts know more about how a disease gets started and how it progresses, that opens up new opportunities for finding ways to put a halt to the damage.

"We could potentially develop therapies to block these T cells, now that we know why the cells are targeting in the brain," says immunologist Cecilia Lindestam Arlehamn, from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology.

Further down the line, being able to spot these PINK1-sensitive T cells in blood samples could lead to Parkinson's disease being diagnosed at an earlier stage – which again helps with treatment and patient support.

While we're still waiting to discover a cure for Parkinson's disease, constant progress is being made in understanding the risk factors involved in its development, and new approaches to tackling it.

"We need to expand to perform more global analysis of the disease progression and sex differences – considering all the different antigens, disease severities, and time since disease onset," says Sette.

The research has been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.