The beast of an earthquake that rattled Mexico in September of last year has turned out to be even more unusual than we knew. Not only did it hit magnitude 8.2 and produce strange lights in the sky, seismologists have now revealed it also cracked a tectonic plate all the way through.

"If you think of it as a huge slab of glass, this rupture made a big, gaping crack," seismologist Diego Melgar of the University of Oregon told National Geographic.

"All indications are that it has broken through the entire width of the thing."

The Tehuantepec, or Puebla-Morelos earthquake took place in the Pacific Ocean off the west coast of Mexico. All along that coast is a tectonic border, between the Cocos Plate in the ocean, and the North American, Caribbean, and Panama Plates that make up the Central American land mass.

As such, the region is no stranger to quakes and tremors as the edge of the Cocos Plate moves beneath the continental plates.

But the Tehuantepec quake on September 7, and the slightly smaller magnitude 7.1 quake that followed on September 19, were both a rare type of "bending" earthquake.

These start off normally, with the tectonic plates colliding, and one starting to slip down underneath the other.

"But then, just as [the Cocos Plate] begins to jut underneath the Mexican mainland, the plate - which is made of dense, heavy rocks - reverses course. It bends upward, sliding itself horizontally beneath the plate Mexico sits on top of. This setup continues for about 125 miles [200 km] or so," Melgar and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México seismologist Xyoli Pérez-Campos explained for The Conversation last month.

"Then, underneath Puebla state - just south of Mexico City - at a depth of about 30 miles [48km] below ground, the subducted plate abruptly changes direction once more. It dives almost vertically downward, plunging itself deep into the Earth's mantle."

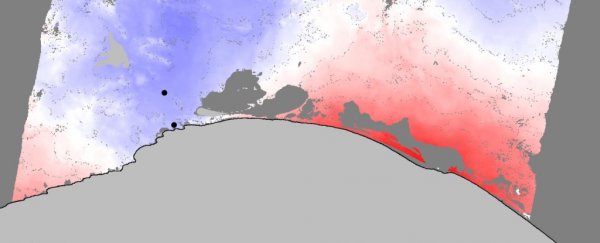

NASA radar data revealing the ground movement of the quake. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/Copernicus)

NASA radar data revealing the ground movement of the quake. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/Copernicus)

This buckles and bends the tectonic plate, a bit like a piece of wood, or a strip of thick rubber. It will stretch up until a certain point - and then it ruptures, resulting in a violent earthquake.

These are called intraplate, or intraslab, earthquakes, because they occur at a considerable distance from the tectonic plate boundary.

Again, though, the Tehuantepec quake was different. When you bend an object, the outside stretches, while the inside is compressed. So it stands to reason that an intraplate earthquake rupture would only affect the top part of the tectonic plate.

But Melgar and his team found that the Cocos Plate ruptured even through the bottom part of the tectonic plate, to the part that should have been compressing.

This was at a depth of about 80 kilometres (50 miles), so the very bottom edge of the tectonic plate.

And that's another problem. At the bottom of the tectonic plate, temperatures reach 1,100 degrees Celsius (2,012 Fahrenheit). This should make the rock too squishy and elastic to rupture - yet according to the team's data, rupture it did.

Why did all this happen? The team's paper puts forth two explanations. The first is that the gravitational force pulling the tectonic plate downwards is pulling it with enough force to counteract the rock's squashed and squishy state.

The second is that seawater could be playing a role too - seeping down into the fault, bringing cooler temperatures and reactions with the minerals in the rock to increase brittleness.

"Deep slip down to the 1,100 °C geotherm requires a substantial deviation from the reference thermal model, suggesting very deep injection of fluids from above and cooling of the fault," the researchers wrote.

"This indicates fluid penetration much deeper than any of the modelling or observations have suggested before. Alternatively, a water-independent process that increases the range of possible temperatures for earthquake slip up to 850 °C could induce shear heating instabilities on localised shear zones."

The Tehuantepec quake's epicenter was on the land side of the fault, which is damaging enough - it destroyed buildings, killed at least 98 people, and injured many more.

It also generated a tsunami, with waves reaching 1.75 metres (5.74 feet) above tide level. Had the quake's epicentre been on the ocean side, that could have been even more devastating, like the devastating 1933 intraplate earthquake off the Japan Trench, which produced 20 metre (65.6-foot) waves.

Knowing what caused the Cocos Plate to rupture could help us plan for and alleviate the human cost of such events in the future.

The team's research has been published in the journal Nature Geoscience.