Deep underground, in the darkness far below the bustling activity on the surface, a community of microbes has been living their best lives in isolation.

What makes these organisms incredibly special is that they have been cut off for billions of years – far longer than any other community of subterranean microbes we've ever seen. This find of living microbes in 2 billion-year-old rock absolutely smashes the previous record of 100 million years.

"So this is a very exciting discovery," says geomicrobiologist Yohey Suzuki of the University of Tokyo.

And it's a significant one: microbes in isolated underground pockets like these tend to evolve more slowly, since they're detached from many of the pressures that drive evolution in more populated habitats.

This means that the microbe community can tell us things we might not have known about microbe evolution here on Earth. But it also suggests that there might be underground microbe communities still alive on Mars, surviving long after the water on the surface dried out.

"We didn't know if 2-billion-year-old rocks were habitable," explains Suzuki.

"By studying the DNA and genomes of microbes like these, we may be able to understand the evolution of very early life on Earth."

The sample of rock was drilled from 15 meters (50 feet) underground from a formation known as the Bushveld Igneous Complex in northeastern South Africa. This formation is huge, a 66,000 square kilometer (25,500 square mile) intrusion into Earth's crust that formed some 2 billion years ago from molten magma cooling below the surface.

Suzuki and his colleagues thought that the rock's formation and evolution over time was likely to be conducive to long-term habitability for microbes. They enlisted the aid of the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program to extract a 30-centimeter (1-foot) long core sample from within the Bushveld Igneous Complex, and set about looking for signs of microbial life.

First, they had to rule out that any microbes they found were indigenous to the habitat, and not the result of contamination from the extraction process. They used a technique they developed several years ago that involves sterilizing the outside of the sample before cutting it into slices to examine its contents.

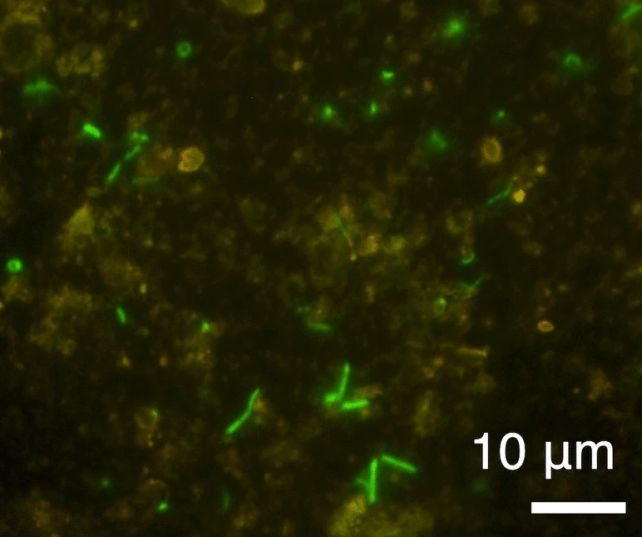

Then, they used a cyanine dye to stain the slices. This dye binds to DNA, so if there is any DNA in the sample, it should light up like a Christmas tree when subjected to infrared spectroscopy. And this is exactly what happened.

The sample was also riddled with clay, which packed veins near the pockets in the rock near the microbial colonies.

The result of this clay packing was multifold: it provided a resource for the microbes to live on, with organic and inorganic materials that they could metabolize; and it effectively sealed the rock, both preventing the microbes from escaping, and preventing anything else from entering – including the drilling fluid.

The microbial community in the rock will need to be analyzed in greater detail, including DNA analysis, to determine how it has changed or not changed in the 2 billion years it has been sequestered away from the rest of life on Earth.

The team will be retrieving more samples from the Bushveld Igneous Complex to help characterize the microbes that can be found therein, and fit them into Earth's evolutionary history.

And, of course, there are the implications for what we might find off Earth.

"I am very interested in the existence of subsurface microbes not only on Earth, but also the potential to find them on other planets," Suzuki says.

"NASA's Mars rover Perseverance is currently due to bring back rocks that are a similar age to those we used in this study. Finding microbial life in samples from Earth from 2 billion years ago and being able to accurately confirm their authenticity makes me excited for what we might be able to now find in samples from Mars."

The research has been published in Microbial Ecology.