Tiny fragments of plastic aren't only finding their way into animals, remote ice caps, oceans, and even the depths of our bodies. They're also seeping through layers of rock, making the emergence of plastics in the geological record a poor marker for the dawn of the human age.

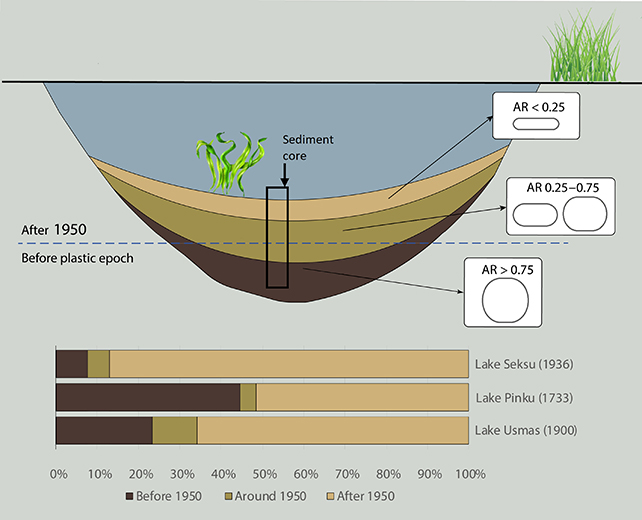

In a new study, sediment samples from three different lakes in Latvia – Seksu, Pinku, and Usmas – were analyzed to see how deep microplastics had sunk. The results showed that smaller particles could travel deeper into the mud, reaching layers laid down before plastic production accelerated at the start of the 1950s.

That makes the presence of plastics in rock strata an unreliable indicator of plastics' proliferation in society, ecologist Inta Dimante-Deimantovica from the Latvian Institute of Aquatic Ecology and an international team of researchers say.

Some geologists have proposed this presence of plastic as a suitable geological starting point to define the official beginning of human's shaping of the planet's surface, known as the Anthropocene.

"We conclude that interpretation of microplastics distribution in the studied sediment profiles is ambiguous and does not strictly indicate the beginning of the Anthropocene Epoch," write the researchers in their published paper.

The results were relatively consistent across the lakes, despite variations in terms of how far away they were from urbanized areas, and the level of access to the public they offered – yet more evidence of how pervasive microplastics have become.

Each sample was dated from modern times back to the early 1700s using independent proxies, providing a reliable measure of their ages. Microplastic particles were found throughout the samples from all sites, with a total of 14 different types of plastic identified by the research term.

Types of microplastic particles included polyamide (used in nylon), polyethylene (often found in packaging), polyurethane (used in foams and fibers), and polyvinyl acetate (found in glues).

The three lakes were chosen because the sediments they sit on have all been extensively studied and dated – which means the team could be certain that smaller plastic particles were reaching older layers of mud.

"We suggest that these findings show a true natural phenomenon, unambiguous downward movement of microplastics in sediment profiles," the researchers write .

All kinds of factors could influence this movement, the researchers say – from the type of the sediment material, to the type of microplastic, to the surrounding environmental conditions – which makes it challenging to study.

What does seem clear is that we're at the stage where we can't get away from microplastics. Experts are still trying to understand what this is doing to our health, but it's becoming clear that the tiny particles are far more pervasive than we ever thought possible.

"It is estimated that only about 9 percent of all plastic ever produced is recycled and 12 percent is incinerated, leading to the conclusion that over 6,000 million metric tons of waste plastic has the potential to leak into the environment and become incorporated in natural cycles and food chains," write the researchers.

The research has been published in Science Advances.