Rocks crumble into the sea as sand. Similarly, the ocean is an inevitable destination of disintegrating human rubbish: microplastics.

Much like a natural sediment, these tiny synthetic granules also make their way into the bellies of the creatures that call the sea home.

But one tiny organism, notorious for its ability to return to life after a trip to space, being frozen or boiled, asphyxiated, even bombarded with radiation, seems to have yet another hidden ability up its wee sleeves. In a study of diverse tiny creatures, tardigrades were seemingly immune to swallowing microplastics.

And that's kind of weird, because all the other small critters in the study gobbled up the stuff.

A team led by zoologist Flávia de França from the Federal University of Pernambuco in Brazil collected samples of meiofauna – intertidal invertebrates between around 45 micrometers to 1 millimeter – from the shallow sediments of a sandy beach on the northeastern coast of Brazil at low tide.

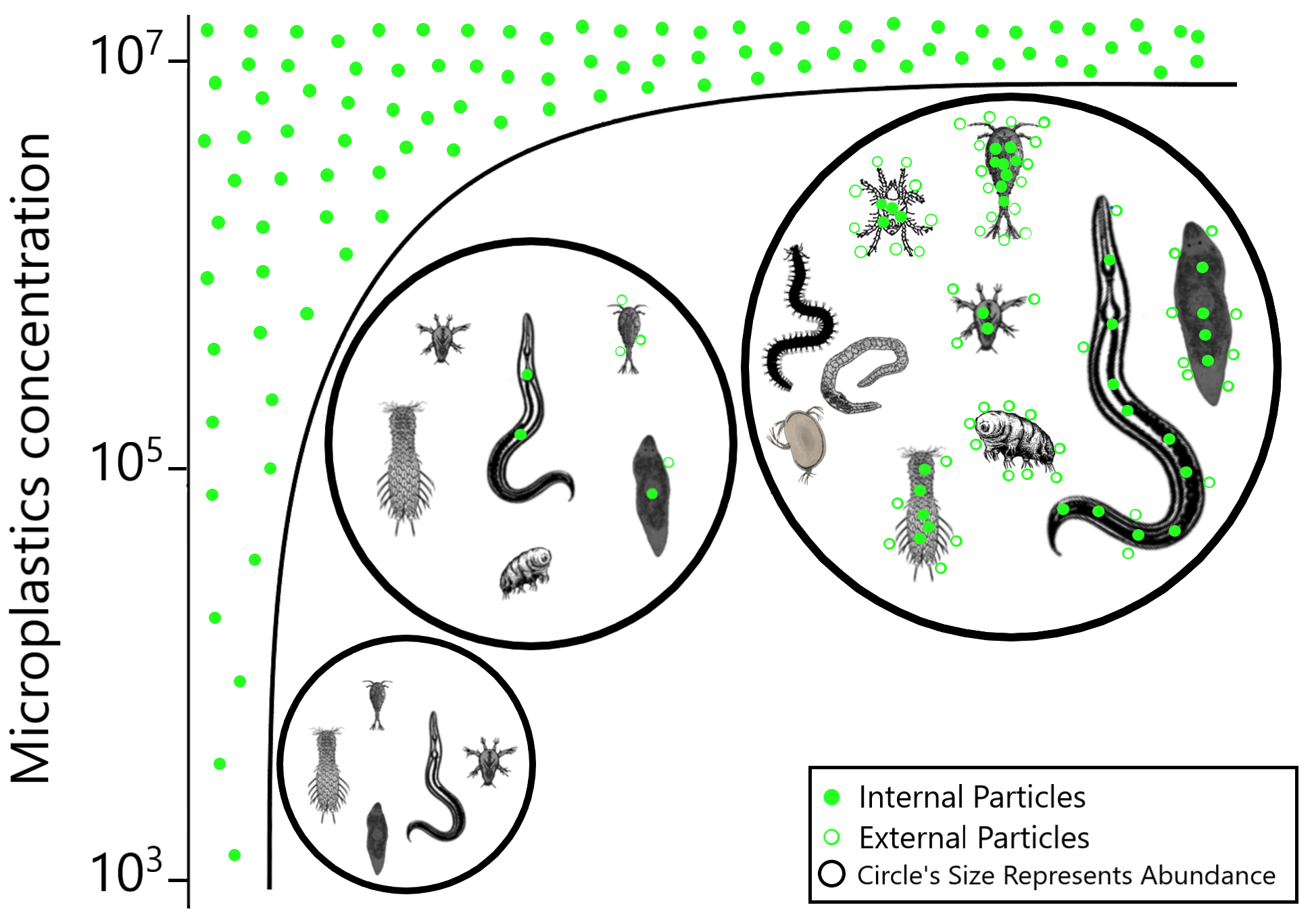

Within these samples they found 5,629 individual organisms, including nematodes, segmented worms, flatworms, bristleworms, seed shrimp, hairybellies, mites, crustaceans and their larvae. And let's not forget the celebrity of the meioverse: the tardigrade.

These critters were kept in tanks designed to mimic the natural environment as best as possible, along with 100 grams of sediment containing varying degrees of plastic particles.

With a radius of around one thousandth of a millimeter, the fluorescent polystyrene microspheres can technically be categorized as 'nanoplastics', but the authors decided not to differentiate these from larger microplastics in light of ongoing debates around the size limits of these particles.

Analysis revesaled all of the tiny creatures swallowed the microplastics except for the tardigrades, which seemed to have the unusual ability to dodge these dubious particles.

They didn't come away completely plastic-free, however. More than half of the waterbears were seen sporting microplastic particles on the surface of their bodies, particularly on their 'legs' (or to be more scientific, their locomotory appendages).

"The absence of microplastic ingestion by Tardigrada likely links to the structure of their feeding apparatus, which includes a mouth tube with a stylet used to pierce and suck rather than ingest prey organisms whole," the authors write.

It's important to note that there is a wide variety of tardigrades, many with differently-shaped body parts, so not all may be protected from our disintegrated rubbish in this way.

While it's fun to discover yet another threat that tardigrades are seemingly impervious to, the study highlights the more serious effects of microplastics at this small but significant scale of life on Earth.

The authors believe this is the first evidence that Turbellarians (flatworms) and Gastrotrichs (hairybacks) consume microplastics.

"Turbellarians can prey on nematodes, copepods, and even individuals of the same taxonomic group," the authors write. "It is therefore plausible that at least part of the ingested microplastics derived from their prey, indicating that microplastics can indeed be transferred up the trophic chain."

They think hairybacks, on the other hand, ingested the microplastics because they mistook them for food. This seems a greater risk given that bacteria grow quickly on the plastics' surface, which to a hairyback must seem like a delicious chocolate coating.

Underlying this research was the question of what impact microplastics are having on species abundance and diversity at this scale. While it was a relatively straightforward relationship between microplastic concentration and ingestion – the more plastic particles, the more the creatures imbibed – the ecological impacts weren't so clear.

"We observed that environmentally relevant concentrations [of microplastics] resulted in a decrease in total meiofauna density and species richness," the authors report, but "a much higher microplastic concentration did not differ from a control without microplastic addition."

The far-reaching impacts of our own species' plastic dependence are alarming. But it's a small comfort to know that some marine tardigrades out there are keeping plastic-free.

This research was published in PeerJ Life and Environment.