Billions of nanometer-wide particles can be released from plastic containers into the food they're holding when they're microwaved, a new study reveals.

A team from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in the US ran experiments using baby food containers made from polypropylene and polyethylene, which are both approved as safe to use by the regulators at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

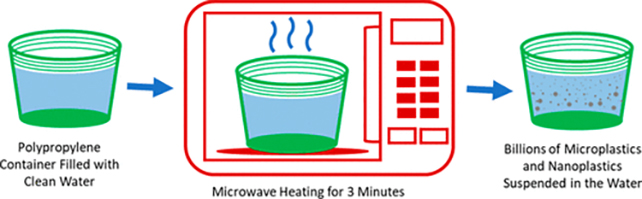

After three minutes of being heated in a 1,000-watt microwave, a variety of liquids put inside the containers were analyzed for microplastics (at least 1/1,000th of a millimeter in diameter) and nanoplastics (even smaller).

Particle numbers varied, but the researchers estimated that 4.22 million microplastic and 2.11 billion nanoplastic particles from only one square centimeter of plastic could be released during those three minutes of microwave heating.

"When we eat specific foods, we are generally informed or have an idea about their caloric content, sugar levels, other nutrients," says civil and environmental engineer Kazi Albab Hussain, from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

"I believe it's equally important that we are aware of the number of plastic particles present in our food."

Microwaving water or dairy products inside polypropylene or polyethylene products is likely to deliver the highest relative concentrations of plastic, the researchers revealed. Particles were also released when food and drinks were refrigerated and stored at room temperature, but significantly fewer in number.

What's not clear right now is what these microscopic plastic particles are doing to us. Studies have shown they can potentially be harmful to the intestine and key biological processes, but it's an area scientists aren't sure about.

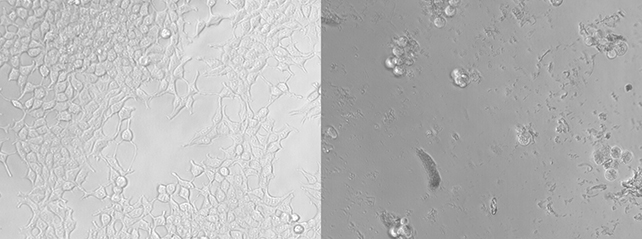

It's probably safe to say that the less plastic we're ingesting the better, though. Embryonic kidney cells cultured by the researchers and exposed to plastic particles at levels of concentrations released by the containers over several days revealed a potential for concern.

The team found 77 percent of the kidney cells exposed to the highest levels of plastic were killed off. While this isn't to say our own kidneys would necessarily be exposed directly to such concentrations, it gives us some idea of the potential toxicity of these microplastics and nanoplastics – particular in developing bodies.

While more detailed research and testing is going to be needed to establish just how damaging these plastic particles can be once they get into the body, it's clear that this is an issue that needs investigating. Our reliance on plastic could be causing significant harm in terms of what we put in our bodies.

"We need to find the polymers which release fewer [particles]," says Hussain.

"I am hopeful that a day will come when these products display labels that read 'microplastics-free' or 'nanoplastics-free'."

The research has been published in Environmental Science & Technology.