It was found along the side of a road in a remote Australian gold rush town. In the old days, Wedderburn was a hotspot for prospectors – it occasionally still is – but nobody there had ever seen a nugget quite like this one.

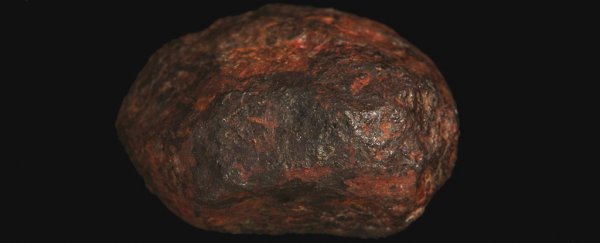

The Wedderburn meteorite, found just north-east of the town in 1951, was a small 210-gram chunk of strange-looking space rock that fell out of the sky. For decades, scientists have been trying to decipher its secrets, and researchers just decoded another.

In a new study led by Caltech mineralogist Chi Ma, scientists analysed the Wedderburn meteorite and verified the first natural occurrence of what they call 'edscottite': a rare form of iron-carbide mineral that's never been found in nature.

“Scientists have discovered a new mineral, one never before seen in nature, lodged inside a meteorite found near Wedderburn in central Victoria.

— Belinda Barnet (@manjusrii) August 31, 2019

Edscottite! https://t.co/j8tt9xqRDn

Since the Wedderburn meteorite's spacey origins were first identified, the distinctive black-and-red rock has been examined by numerous research teams – to the extent that only about one-third of the original specimen still remains intact, held within the geological collection at Museums Victoria in Australia.

The rest has been taken away in a series of slices, extracted to analyse what the meteorite is made from. Those analyses have revealed traces of gold and iron, along with rarer minerals such as kamacite, schreibersite, taenite, and troilite. Now we can add edscottite to that list.

The edscottite discovery – named in honour of meteorite expert and cosmochemist Edward Scott from the University of Hawaii – is significant because never before have we confirmed that this distinct atomic formulation of iron carbide mineral occurs naturally.

Such a confirmation is important, because it's a pre-requisite for minerals to be officially recognised as such by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA).

A synthetic version of the iron carbide mineral has been known about for decades – a phase produced during iron smelting.

But thanks to the new analysis by Chi Ma and UCLA geophysicist Alan Rubin, edscottite is now an official member of the IMA's mineral club, which is more exclusive than you might think.

"We have discovered 500,000 to 600,000 minerals in the lab, but fewer than 6,000 that nature's done itself," Museums Victoria senior curator of geosciences Stuart Mills, who wasn't involved with the new study, told The Age.

As for how this sliver of natural edscottite ended up just outside of rural Wedderburn can't be known for sure, but according to planetary scientist Geoffrey Bonning from Australian National University, who wasn't involved with the study, the mineral could have formed in the heated, pressurised core of an ancient planet.

Long ago, this ill-fated, edscottite-producing planet could have suffered some kind of colossal cosmic collision – involving another planet, or a moon, or an asteroid – and been blasted apart, with the fragmented chunks of this destroyed world being flung across time and space, Bonning told The Age.

Millions of years later, the thinking goes, one such fragment landed by chance just outside Wedderburn – and our understanding of the Universe is the richer for it.

The findings are reported in American Mineralogist.