The oceans are full of plastic. We know it, and we know it's a big problem. What we don't know is precisely how big the problem is.

A fluorescent dye could help scope out the tiniest pieces of garbage in our marine environments, allowing researchers to map oceanic waste in unprecedented detail and just maybe help us find solutions to this growing environmental crisis.

Waste that accumulates in gyres, often described as Great Garbage Patches, often shocks us with its sheer scale.

But it's the tiny bits we don't see that are as much of a concern, if not more so.

Particles smaller than 5 millimetres (0.2 inches) known as microplastics can be found as tiny beads in cosmetics and cleaning products, fibres in garments, or form from larger plastics breaking down.

As such, they are estimated to be far more abundant than the chunky bottles and floating bags we can see. Just how much more, nobody really knows.

Research led by the University of Warwick in the UK has found a practical solution for detecting microplastics in field samples.

Tiny pieces of plastic waste on the scale of tens of micrometres aren't exactly easy to distinguish from other pieces of natural flotsam, even with a decent microscope.

As tempting as it is to think of these miniscule shreds of rubbish as 'out of sight, out of mind', they're just a much of an issue for marine species as the turtle-choking plastic bags that larger animals mistaken for tasty jellyfish.

Just recently, researchers found coral polyps didn't just swallow them up – they did so with relish, seeming to actually like the flavour.

That's not to mention the variety of plastic materials that shed persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic (PBT) compounds into the food chain.

So getting a grip on the scale and distribution of microplastics is clearly a high priority.

"Current methods used to assess the amount of microplastics mostly consist in manually picking the microplastics out of samples one by one," says marine ecologist Gabriel Erni-Cassola.

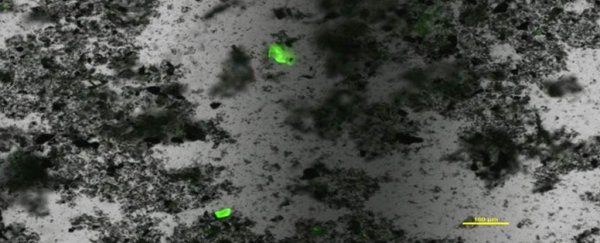

To help make the plastics stand out from similar-looking bits of gunk, the researchers investigated the use of "Nile red", a fluorescent dye that lights up when it comes into contact with the right kinds of chemicals.

Preliminary tests on different plastic polymers showed the dye was up to the job of making microplastics stand out.

To make sure it didn't mark similar materials such as fatty substances or tiny wood fragments, they flushed samples with nitric acid, which proved efficient at digesting all kinds of biogenic matter.

Out in the field, the team took samples of beach sand and trawled the surface water from the coast around the town of Plymouth and analysed them for microplastics using both traditional methods and their staining technique.

They found a much larger amount of microplastics under 1 millimetre (0.04 inches) in size than they'd predicted, and significantly more than they'd have found using traditional methods alone.

The number one culprit for these hidden, smaller variety microplastics seems to be polypropylene – the stiff polymers we use in everything from ropes to banknotes to packaging.

"Using this method, a huge series of samples can be viewed and analysed very quickly, to obtain large amounts of data on the quantities of small microplastics in seawater or, effectively, in any environmental sample," says Erni-Cassola.

Previous studies have determined that 99 percent of the plastic waste that we believe to be entering the ocean can't be detected, meaning it's either too small to see or is hiding inside the digestive systems of marine life.

This new method seems to have spotted at least a portion of it.

"Have we found the lost 99 percent of missing plastic in surface oceans?" asks Joseph A. Christie-Oleza, a microbiologist and a co-author on the study.

"Obviously this method needs to be implemented in future scientific surveys to confirm our preliminary findings."

Tracking the fate of microplastics will certainly help inform future policies on waste management and industry regulations.

Meanwhile, the challenge of weaning ourselves off our insatiable love of plastics and finding a way to deal with the waste remains.

This research was published in Environmental Science & Technology.