While the Milky Way and other giant disc galaxies roam our Universe today, the early Universe was home to compact massive galaxies that apparently weren't so lucky. These compact elliptical galaxies formed their stars early-on and then seemingly vanished.

The fate of these compact massive galaxies has remained something of a mystery since they were first detected a decade ago. But now researchers from Swinburne University of Technology in Australia believe they've solved the puzzle.

"When our Universe was young, there were lots of compact, elliptical-shaped galaxies containing trillions of stars," said Alister Graham, an astronomer at Swinburne University of Technology.

"Due to the time it takes for light to travel across the vastness of space, we actually see these distant galaxies as they were in our young Universe. However in the nearby and thus present-day Universe very few such spheroidal stellar systems have been observed."

There is a popular theory for the exceedingly rare presence of these galaxies in modern times. It suggests that, over time, violent mergers led to their mutual destruction or transformations, to form new, giant elliptical-shaped galaxies.

But there's a problem. There haven't been enough galactic collisions to account for the significant reduction in the number of these compact galaxies.

Graham and his team at Swinburne think they've solved the riddle. In fact, the team thinks they have found the compact galaxies themselves.

In a study posted on arXiv.org, the researchers say they have located 21 compact spheroids in "our own backyard", which had previously been overlooked because they were "encased in stellar discs". This made them appear larger and somewhat paradoxically more difficult to locate.

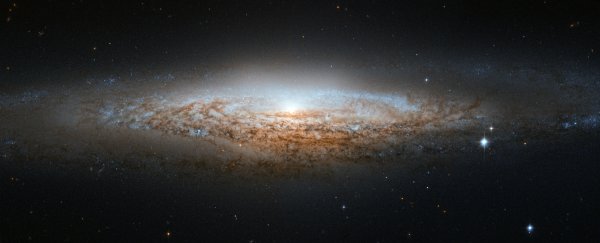

"They were hiding in plain sight," said co-author Bililign Dullo in a statement. "The spheroids are cloaked by discs of stars that were likely built from the accumulation of hydrogen gas and smaller galaxies over the intervening eons."

What's more, the researchers say the number of such hidden systems, per unit volume of space, roughly matches the number density of compact massive galaxies in the early Universe.

"The galactic dinosaurs of our Universe are not extinct," said Graham in the Swinburne press release. "They are simply embedded in large, relatively thin, discs of stars."

Due to the way modern galaxy surveys are conducted, it has become a common practice to treat individual galaxies as single entities, the researchers say in the press release.

To locate the missing compact galaxies, the Swinburne team needed to disentangle the constituent parts of each galaxy they observed – particularly the spherical cluster of stars at a galaxy's core, known as a bulge, and the outer disc.

"While the inner component is compact and massive, the full galaxy sizes are not compact," said PhD student and co-author of the study Giulia Savorgnan. "This explains why they had been missed; we simply needed to better dissect the galaxies rather than consider them as single objects."

"While we do not deny that there has been galaxy size evolution," the authors write, "we are suggesting a fundamentally different formation model which presents a dramatic shift in our way of thinking about how the compact massive objects … have actually evolved in our Universe."

Their study is available on arXiv.org and will be published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Want to be involved in Universe-changing research? Find out more about studying at Swinburne University of Technology.