For years, researchers have known that carbon, when arranged in a certain way, can be very strong.

Case in point: graphene. Graphene, which was heretofore, the strongest material known to man, is made from an extremely thin sheet of carbon atoms arranged in two dimensions.

But there's one drawback: while notable for its thinness and unique electrical properties, it's very difficult to create useful, three-dimensional materials out of graphene.

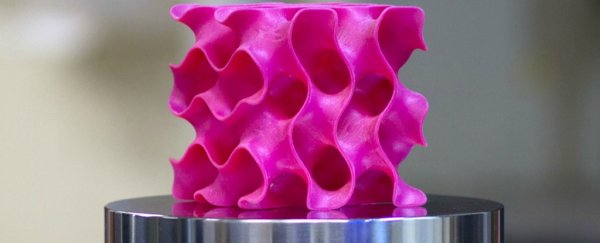

In January last year, a team of MIT researchers discovered that taking small flakes of graphene and fusing them following a mesh-like structure not only retains the material's strength, but the graphene also remains porous.

Based on experiments conducted on 3D printed models, researchers have determined that this material, with its distinct geometry, is actually stronger than graphene – making it 10 times stronger than steel, with only 5 percent of its density.

The discovery of a material that is extremely strong but exceptionally lightweight will have numerous applications.

As MIT reports:

"The new findings show that the crucial aspect of the new 3-D forms has more to do with their unusual geometrical configuration than with the material itself, which suggests that similar strong, lightweight materials could be made from a variety of materials by creating similar geometric features."

Below you can see a simulation results of compression (top left and i) and tensile (bottom left and ii) tests on 3D graphene:

Credit: Zhao Qin

Credit: Zhao Qin

"You could either use the real graphene material or use the geometry we discovered with other materials, like polymers or metals," said Markus Buehler, head of MIT's Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE), and the McAfee Professor of Engineering.

"You can replace the material itself with anything. The geometry is the dominant factor. It's something that has the potential to transfer to many things."

Large scale structural projects, such as bridges, can follow the geometry to ensure that the structure is strong and sound.

Construction may prove to be easier, given that the material used will now be significantly lighter. Because of its porous nature, it may also be applied to filtration systems.

This research, said Huajian Gao, a professor of engineering at Brown University, who was not involved in this work, "shows a promising direction of bringing the strength of 2D materials and the power of material architecture design together".

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.