For humans to ever venture out among the stars, we will have to solve some hefty logistical problems.

Not the least of these is the travel time involved. Space is so large, and human technology so limited, that the time it would take to travel to another star presents a significant barrier.

The Voyager 1 probe, for instance, would take 73,000 years to reach Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to the Sun, at its current speed.

Voyager launched more than 40 years ago, and more recent spacecraft might be expected to travel faster; even so, the journey would still take thousands of years with our current technology.

One potential solution would be generation ships, which would see multiple generations of space travelers live and die before reaching the final destination. Another would be artificial hibernation, if it could be successfully implemented.

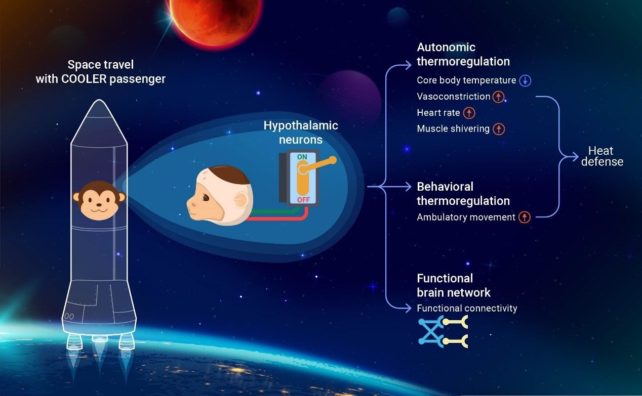

This is what scientists from the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology (SIAT) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have started to investigate; not in humans, but in monkeys, by chemically triggering a state of hypothermia.

"Here, we show that activating a subpopulation of preoptic area (POA) neurons by a chemogenetic strategy reliably induces hypothermia in anesthetized and freely moving macaques," the researchers write in their paper.

"Altogether, our findings demonstrate the central regulation of body temperature in primates and pave the way for future application in clinical practice."

Hibernation and its slightly less comatose state, torpor, are physiological states that allow animals to withstand adverse conditions, like extreme cold and low oxygen.

The body temperature lowers, and metabolism slows to a crawl, keeping the body in a bare-bones 'maintenance mode' – the bare minimum to stay alive while preventing atrophy.

This can be found across several animals, including warm-blooded mammals, but very few primates. Neuroscientists Wang Hong and Dai Ji of SIAT wanted to see if they could artificially induce a state of hypometabolism, or even hibernation, in primates by chemically manipulating neurons in the hypothalamus responsible for sleep and thermoregulation processes – the preoptic neurons.

The research was performed on three young male crab-eating monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). In both anesthetized and non-anesthetized states, the researchers applied drugs designed to activate specific modified receptors in the brain, known as Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs, or DREADDs.

Then, the scientists studied the results using functional magnetic resonance imaging, behavioral changes, and physiological and biochemical changes.

"To investigate the brain-wide network as a consequence of preoptic area (POA) activation, we performed fMRI scans and identified multiple regions involved in thermoregulation and interoception," Dai says.

"This is the first fMRI study to investigate the brain-wide functional connections revealed by chemogenetic activation."

The researchers found that a synthetic drug called Clozapine N-oxide (CNO) reliably induced hypothermia in both the anesthetized and awake states in the macaques.

However, in anesthetized monkeys, the CNO-induced hypothermia resulted in a drop in core body temperature, preventing external heating. The researchers say that this demonstrates the critical role POA neurons play in primate thermoregulation.

The researchers recorded behavioral changes in the awake monkeys and compared them to those of mice with induced hypothermia. Typically, mice decrease activity, and their heart rate lowers in an attempt to conserve heat.

The monkeys, by contrast, showed an increased heart rate and activity level and, in addition, started shivering. This suggests that thermoregulation in primates is more complex than in mice; hibernation in humans (if it can be done at all) will need to take this into account.

"This work provides the first successful demonstration of hypothermia in a primate based on targeted neuronal manipulation," Wang says.

"With the growing passion for human spaceflight, this hypothermic monkey model is a milestone on the long path toward artificial hibernation."

The research has been published in The Innovation.