We're naturally reluctant to abandon something we've sunk time, effort, and money into, even when the best option is to just walk away – and it turns out that monkeys feel exactly the same, according to a new study.

This "sunk costs" phenomenon can apply to our relationships, home improvements, books, video games, car repairs, side hustles, TV shows, and plenty more besides. We keep going because we're already invested, even when it becomes self-defeating.

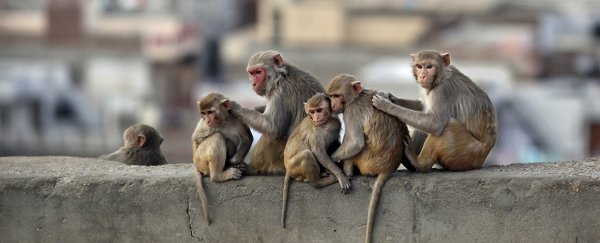

That the same trait is noticeable in the capuchin monkeys and rhesus macaques in this study suggests there's something deep in our evolutionary past that convinces us to try and recover a reward from our sunk costs, no matter how unlikely it is to happen.

"These results show that sunk cost effects can arise in the absence of human-unique factors and may emerge, in part, because persisting can resolve uncertainty," write the researchers in their published paper.

In this study, the animals were asked to follow a moving target on a computer screen with a joystick. If they managed to track it, they got a reward; if they didn't, a new round started, and they could try again.

Rounds lasted for 1, 3, or 7 seconds (a single second actually seems a lot longer to a monkey), and most rounds lasted for just 1 second. In other words, if the monkeys didn't get a treat after the first second, it was better to quit and start a new round to get a reward as soon as possible.

The monkeys typically carried on, though. This effect was especially noticeable for the seven macaques, but the 26 capuchins struggled to let go as well. If the animals got a signal that more work was needed for a reward, the sunk cost behaviour was less frequent, but it was still evident.

The researchers say this shows that the chasing of sunk costs is something we've evolved to do, and is a deep instinct we share with a lot of species. The same phenomenon has also been demonstrated in studies of pigeons and rats before.

"They persisted five to seven times longer than was optimal," says neuroscientist Sarah Brosnan, from Georgia State University. "The longer they had already tried, the more likely they were to complete the entire task."

The monkeys' behaviour also shows that specifically human factors – our ability to rationalise, or our need to maintain our public reputation – may not play a huge role in our tendency to persist with something for too long.

A deep drive to persist seems to be present in multiple species, and of course, patience and commitment often pay off in the wild: in foraging for food, hunting down prey, waiting for eggs to hatch, building nests, and so on.

As supposedly more intelligent beings, we should be more able than most animals to realise when an activity or endeavour is no longer good for us, and make a sensible decision – though it's easier said than done.

"We're predisposed to keep trying," says Brosnan. "And when we find ourselves sticking with things, we should also be a little reflective. Do I have a good reason to keep trying? Or should I leave with no reward, because it will save me more in the long run?"

"That's really hard to do. But hopefully we can use our cognitive abilities to help us overcome the emotional heartache of occasional sunk costs."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.