Birds-of-paradise have some of the most famous mating displays in the world, but there's more to their colorful rhythmic gymnastics than initially meets the human eye.

For the first time, scientists have discovered these spectacular avians absolutely glowing with gorgeousness in a dark room.

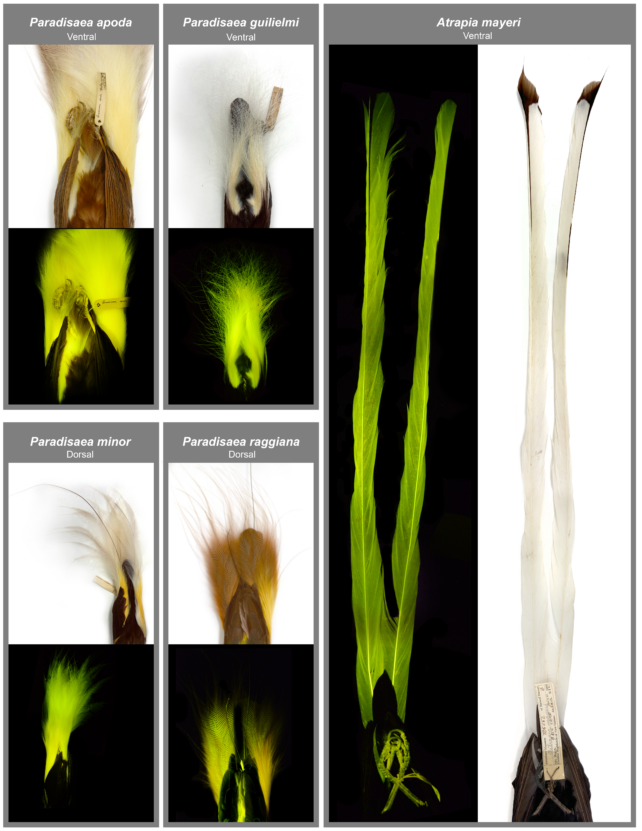

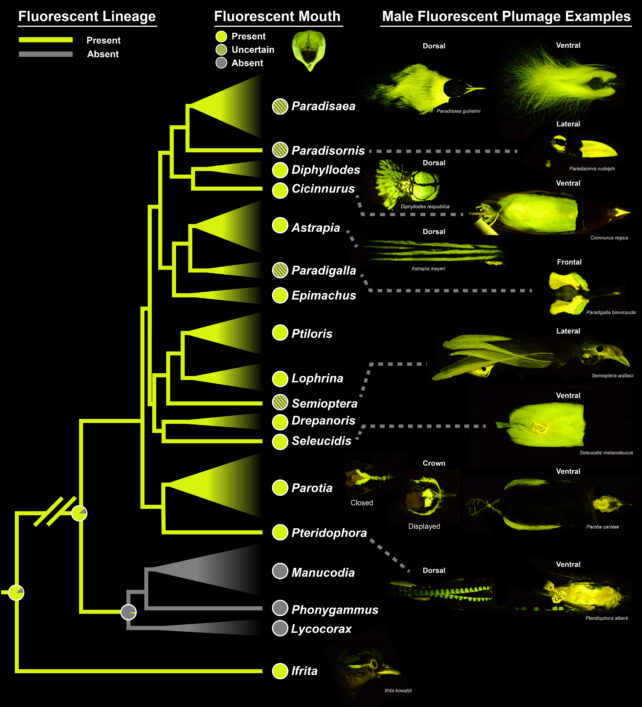

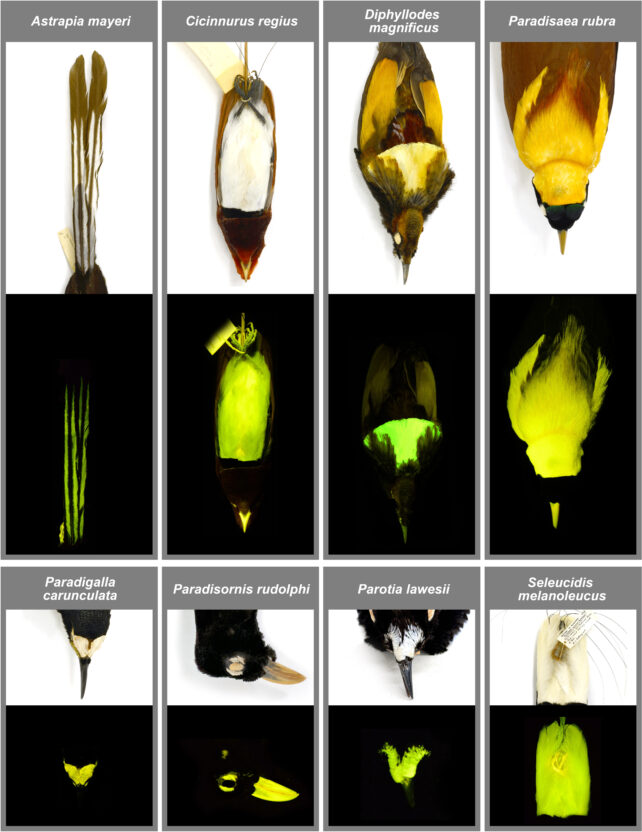

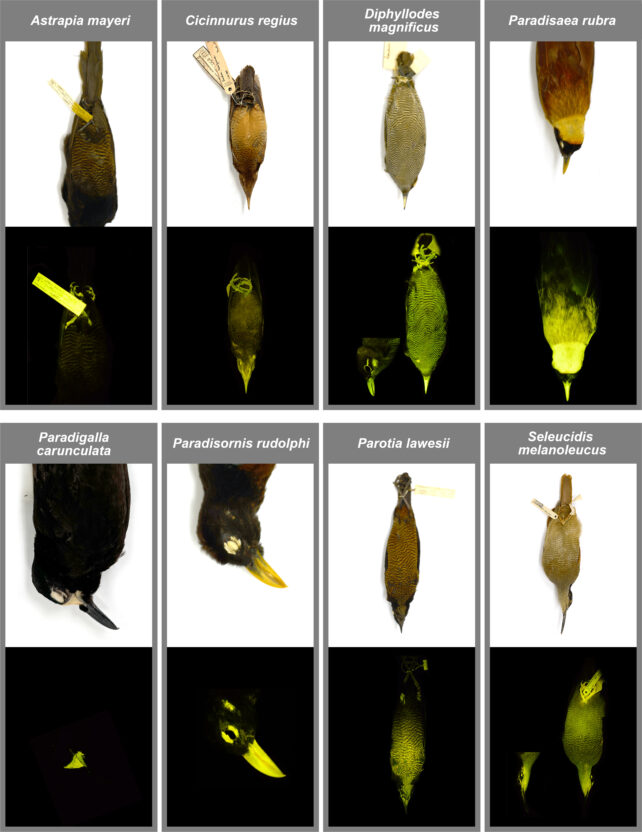

Researchers at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) combed through the available archives and found that all 37 core bird-of-paradise species in Australia, New Guinea, and Indonesia are biofluorescent. Only a few fringe family members fail to glow under ambient UV or blue light.

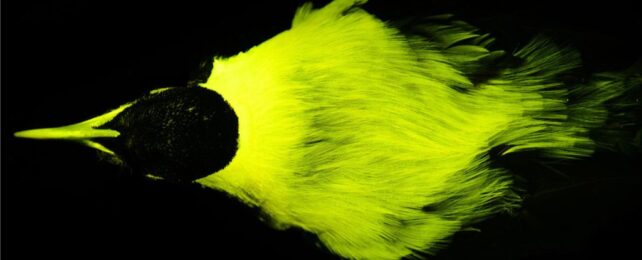

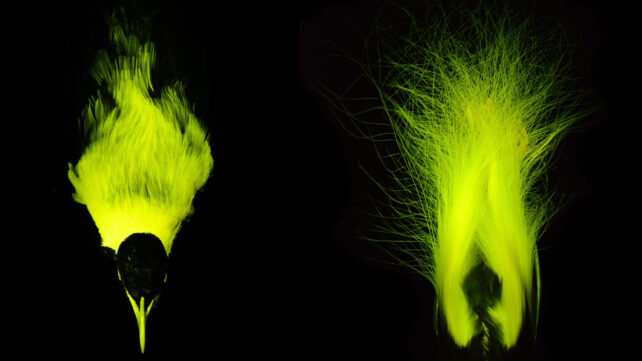

Most male birds tested possess brightly fluorescent heads, napes, bills, and plumes that glimmer with green or greenish-yellow hues. Some even have fluorescent legs, feet, tails, and rings around their eyes.

Many of these mysteriously colorful patches are starkly bordered by dark feathers with no fluorescence, and these parts of the body are often used in mating displays, when males flap, flutter, sway, bop, hang, and pose in an elaborate, attention-seeking dance that varies from species to species.

The current research was conducted among deceased birds of paradise, so it's unknown why these biofluorescent bits exist, or how the birds use them in the wild.

But because bird-of-paradise courtship relies on bright, colored plumage, lead author, evolutionary biologist Rene Martin, argues, "It seems fitting that these flashy birds are likely signaling to each other in additional, flashy ways", making their display even more eye-catching.

Some male birds may even open up their glowing bills to show the female just how deep their beauty goes.

Before or during their courtship display in the wild, some male birds-of-paradise will raise their wings up to surround their face, creating what Martin and her colleagues describe as "a dark black halo".

In the center of this frame, the bird will open their bright, biofluorescent mouth for extended periods of time, up to 30 seconds or longer.

The researchers suspect that all core bird-of-paradise species possess fluorescent regions inside their mouths. Oftentimes, however, museum samples of these birds are preserved with beaks closed.

Other males from different species may use the bright fluorescent patches on the crown of their head as their 'feature' piece, contrasted by a black 'skirt' of feathers spread out below.

Because females sit on a branch above the male to watch his performance, this fluorescent head would pop from the darkness.

That's an interesting hypothesis, but it only explains one-half of the picture.

Thirty-six, possibly 37, species of female bird-of-paradise were also found to fluoresce, albeit less brightly than the males, and their glowing parts were typically limited to the patterned and mottled feathers on their chest and belly.

Sometimes, the rings around female eyes also glowed, possibly used as a signal to other birds that they are watching.

More research is needed but it's possible females are using this biofluorescence for "simultaneous camouflage and communication", argues the team at AMNH.

Many bird species can see spectra in the ultraviolet sensitive (UVS) and violet sensitive (VS) wavelength ranges, and birds-of-paradise are thought to possess this skill as well.

These stunning creatures live in woodland habitats where an abundance of high-energy ambient UV and blue light trickles through the canopy to the forest floor, allowing for their skin or feathers to absorb certain wavelengths of light and fluoresce.

Before now, official accounts of biofluorescence among birds existed just for auks, puffins, penguins, nocturnal owls, nightjars, parrots, and bustards. What's more, only studies on auks, parrots, and puffins had considered how these elaborate feathers might play a role in courtship and copulation.

"Despite there being over 10,000 described avian species, with numerous studies that have documented their bright plumage, elaborate mating displays, and excellent vision, surprisingly very few have investigated the presence of biofluorescence," says museum curator John Sparks, who started this research at AMNH roughly a decade ago.

Sparks' and his colleagues' findings add to a growing list of overlooked organisms that may use biofluorescence, including platypuses, wombats, and sea turtles. What role, if any, these vivid colors play in the wild is a mystery that scientists are just beginning to crack.

The study was published in Royal Society Open Science.