Scientists have located the body's toggle for breaking down brown fat – a type of adipose tissue that burns calories to generate warmth.

In experiments on mice, removing the 'off switch' for brown fat metabolism forced them to continue breaking down blood sugar and fat as if their core temperature depended on it.

A similar mechanism seems to also exist in brown fat cells derived from humans.

The international team of researchers behind the experiments, who hail from Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and Spain, hope that their findings will "pave the way to reactivate [brown adipose tissue] function and mitigate obesity" and metabolic syndromes associated with obesity.

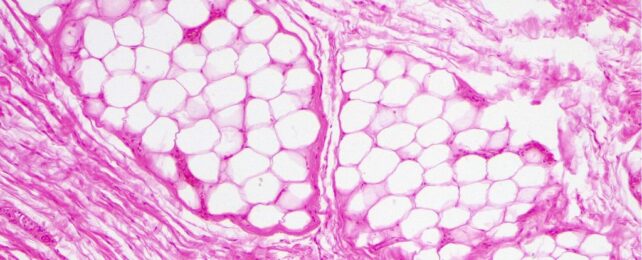

Brown fat, or brown adipose tissue, got its name because unlike white fat, which contains few mitochondria, its cells are packed with dark, iron-rich energy centers.

The abundance of these 'powerhouses' is necessary because one of brown fat's main jobs is to burn blood sugar and fat to heat the body and maintain its core temperature in the cold, as opposed to white fat's storage which is primarily for insulation and protection.

Historically, scientists thought brown fat was only present in small mammals and human newborns, and yet just over a decade ago, researchers identified significant brown fat stores that are active and functional in most healthy men and women.

These stores exist at lower percentages than in newborns but they still help warm the adult body when it gets cold. They appear to also help control blood sugar and insulin levels. In those who are overweight or obese, evidence suggests brown fat tends to be lacking.

Over the years, studies on humans and rodents have found the molecular 'on switch' that kicks brown fat metabolism into gear. This switch increases energy expenditure and the consumption of fatty acids and glucose.

The unfortunate news is that the on-switch is quickly turned off, the European research team explains. Their study, led by Sajjad Khani from the University of Cologne in Germany and Hande Topel from the University of Southern Denmark, has now identified brown fat's corresponding 'off switch', using advanced technology to find unknown proteins associated with the metabolism.

In mice kept at cold temperatures, the protein, AC3-AT, seems to be quickly triggered to tell the metabolism to cool off. It stops the mammal body from expending energy at a high rate for too long, even in chronic coldness. Evolutionary, this makes sense, but it can get in the way of potential metabolic treatments that attempt to manipulate brown fat.

In experiments, when scientists fed mice a high-fat diet for 15 weeks, those animals that lacked AC3-AT proteins accumulated less fat in their body and were metabolically healthier than the control group.

"When we investigated mice that genetically didn't have AC3-AT, we found that they were protected from becoming obese, partly because their bodies were simply better at burning off calories and were able to increase their metabolic rates through activating brown fat," explains Topel.

Even more promising, Topel and colleagues found the expression of this protein was also present in human cells and was induced by cold temperatures in a similar way.

"Looking ahead, we think that finding ways to block AC3-AT could be a promising strategy for safely activating brown fat and tackling obesity and related health problems," says Topel.

Brown fat was initially discovered in small mammals, but its presence and role in the human body is still very much a mystery. The current research represents a fascinating new lead.

The study was published in Nature Metabolism.