Scientists have caught a type of immune cell invading nerve cells, discovering a possible cause of fibromyalgia in an animal model of the disease.

Fibromyalgia is characterized by chronic, widespread, and debilitating pain, thought to be triggered by a process known as central sensitization. This is where the body's central nervous system mistakenly amplifies nerve signals passing through the brain and spinal cord, sensitizing the person to more pain in a vicious feedback loop.

But our understanding of the disease, which affects mostly women, is rapidly shifting with long overdue research, and studies have pointed toward changes in the peripheral or outer nervous system also.

A 2021 study introduced antibodies from people with fibromyalgia into mice, thereby increasing the test animals' sensitivity to pain. The investigation's findings made a strong case for the syndrome operating as an autoimmune disorder – or at least one where immune cells play a key role.

"Growing evidence demonstrates an intricate bidirectional interaction between immune cells and sensory neurons," writes the research team, led by molecular and cell biologist Sara Caxaria from the Queen Mary University of London.

Using a similar approach to the 2021 study, the researchers introduced immune cells called neutrophils collected from patients with fibromyalgia into mice.

The otherwise healthy animals became sensitized to pain only with the human neutrophils circulating in their system, but not when antibodies, serum, or other immune cells from fibromyalgia patients were injected or cells from healthy volunteers.

Neutrophils are typically involved in the innate immune response, the body's first line of defense against invading pathogens. It's rapid and non-specific, a blunt assault on any intruders deployed at the first signs of infection.

Research has found a surprisingly high number of neutrophils in the bloodstream of fibromyalgia patients, along with elevated levels of the inflammatory cytokines neutrophils produce.

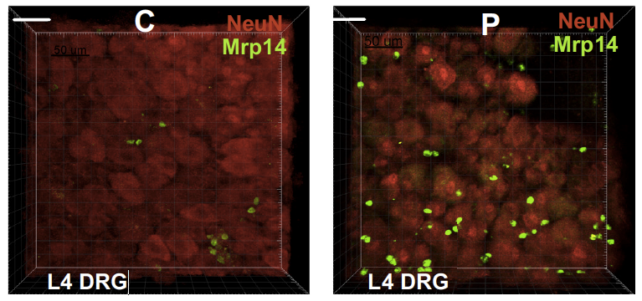

Neutrophils are not normally found within tissues of the nervous system, only in instances of injury or disease. Yet in a series of imaging experiments, the human neutrophils collected from fibromyalgia patients were seen invading bundles of sensory nerves called ganglia in the animal's peripheral nervous system.

That invasion was swift, with the mice's spinal cord cells becoming overly responsive to painful stimuli within just an hour of the human cells flooding their bloodstream.

Of course, this is an animal model replicating a human disease that leaves out conditions that so often accompany fibromyalgia (and other types of chronic pain) such as sleep dysfunction, stress, anxiety, and depression. But the findings do suggest that neutrophils play a role beyond acute inflammatory pain, possibly tripping the nervous system into a state of lasting chronic pain.

Appreciating how neutrophils infiltrate nerve cells and send pain processing awry also opens the door to potential treatment approaches for fibromyalgia. When the researchers depleted mice primed to the pain of neutrophils, the onset of persistent widespread pain was measurably delayed.

"These data demonstrate that neutrophils are fundamental for the development of chronic widespread pain through infiltration of peripheral sensory ganglia," Caxaria and colleagues write.

No doubt researchers will continue to debate whether fibromyalgia has a neurological origin or an immunological one. Though the results from this study strengthen the evidence for the latter, they have introduced questions of their own. Caxaria and colleagues were unable to replicate the findings of the 2021 study and elicit abnormal pain responses in mice with just the antibodies from fibromyalgia patients.

More research could help tease out the subtle differences in people's pain experiences that may have influenced the inconsistent results.

Why fibromyalgia and autoimmune disorders affect women more often than men also remains a mystery. Both male and female mice in this latest study were hypersensitized to pain, "and therefore the underlying mechanisms for sex differences in the prevalence of fibromyalgia remain to be determined," the researchers note.

The study has been published in PNAS.