Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is one of the most common chronic pain conditions out there, yet we still know shockingly little about it.

For decades, the debilitating condition - marked by widespread pain and fatigue - has been vastly understudied, and while it's commonly thought to originate in the brain, no one really knows how fibromyalgia starts or what can be done to treat it. Some physicians maintain it doesn't even exist, and many patients report feeling gaslit by the medical community.

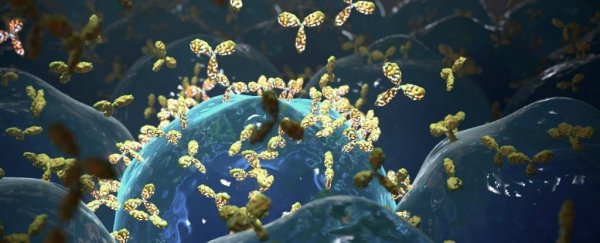

New research on mice has now found further evidence that fibromyalgia is not only real, but may involve an autoimmune response as a driver for the illness.

When researchers injected mice with antibodies from 44 humans living with the syndrome, they noticed several classic symptoms in the animals, including muscle weakness, tenderness, and increased sensitivity to heat and cold. All around their bodies, pain-sensing nerves became far more sensitive.

Meanwhile, control mice that were injected with antibodies from 39 healthy people showed no such symptoms.

Because these pain-causing antibodies were not found in the central nervous system of patients, the authors suspect fibromyalgia is a disease of the immune system, not a disease that originates in the brain's pain pathways.

That idea isn't altogether surprising - 80 percent of people with fibromyalgia are women, and women are far more impacted by autoimmune diseases - but it is controversial, as brain imaging studies have left many scientists thinking fibromyalgia is neurological in origin.

In recent years, however, genetic studies have found evidence that fibromyalgia could be an autoimmune condition, at least among a subset of patients.

"When I initiated this study in the UK, I expected that some fibromyalgia cases may be autoimmune," says Andreas Goebel, who studies pain medicine at the University of Liverpool.

As it turned out, however, the same antibodies that caused pain in mice were found in all 44 patients living with fibromyalgia, in both the United Kingdom and Sweden.

The study is only based on how human antibodies work in mice, not human bodies, and further research will be needed to determine how the presence of these antibodies actually causes pain and fatigue.

That said, the findings indicate fibromyalgia may, in fact, have an autoimmune origin and not a neurological one. The pain-causing antibodies identified in the study were able to bind to both mouse and human neurons, which means these markers could be driving some of the neurological changes we are seeing in brain scans.

If this is true, it helps explain why gentle aerobic exercise and drug therapies, like antidepressants, don't work for many patients; they might not be getting to the root of the problem.

Drugs that focus on controlling antibody levels, on the other hand, could be far more effective.

A few weeks after the experiment, when mice had cleared all pain-causing antibodies from their system, the animals went back to normal.

This suggests fibromyalgia symptoms can be rapidly reversed if the pain-causing antibodies are controlled.

Luckily, we already have some drugs that can do that on the market. Now, we just need to put them to the test.

"Our work has uncovered a whole new area of therapeutic options and should give real hope to fibromyalgia patients," says neuroscientist David Andersson from King's College London.

Andersson hopes to bolster his research by conducting similar mouse studies using antibodies from those with long COVID or myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). These are two chronic conditions that have many overlapping symptoms with fibromyalgia and have recently been connected to autoimmune issues as well.

The question over whether fibromyalgia is neurological or immunological is still under debate, but this new evidence is certainly casting doubt over previous assumptions.

"If these results can be replicated and expanded upon, then the prospect of a new treatment for people with fibromyalgia would be extraordinary," Des Quinn, the chair of Fibromyalgia Action UK, told The Guardian.

"However, the results need further confirmation and investigation before the outcomes can be applied universally."

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.