It's no secret that being born into a poor family can give you a rough start in life, but new research has shown that the amount of money parents have can actually change a child's brain connectivity, and put them at greater risk of depression.

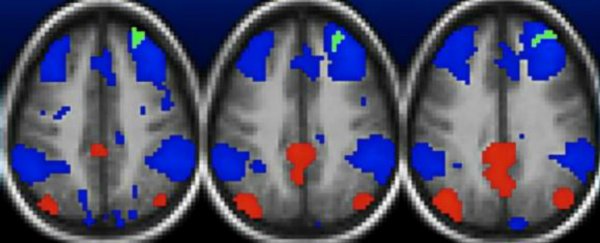

A team from Washington University St Louis analysed functional MRI scans of 105 children aged between 7 and 12, and found that key structures in the brain connect differently in poor children when compared to kids from a wealthy family. Importantly, those brain structures influence how children learn, and regulate their stress levels and emotions.

"Our past research has shown that the brain's anatomy can look different in poor children, with the size of the hippocampus and amygdala frequently altered in kids raised in poverty," said lead researcher Deanna Barch. "In this study, we found that the way those structures connect with the rest of the brain changes in ways we would consider to be less helpful in regulating emotion and stress."

The study also found that kids who were poor in preschool were more likely to be depressed at age 9 or 10, when compared to their more affluent peers.

Poverty in this case was measured using an income-to-needs ratio, which takes into account a family's size and their annual income. It's already known that when things are tight at home, children are at a higher risk for psychiatric illnesses and poor educational outcomes.

Although we don't quite know why this link exists, researchers hypothesise that it's a result of environmental factors such as stress, poor nutrition, exposure to cigarette smoke and other toxins, and limited educational opportunities.

Now the Washington University St Louis team has also been able to show one of the potential pathways through which poverty could lead to emotional disorders.

The brain structures they were looking at were the hippocampus - which is known to be important in learning, memory, and emotion - and the amygdala - involved in stress and emotion. After studying the brain scans, the team found that the poorer a kid's family was, the weaker the connection between their hippocampus and amygdala and other parts of the brain.

In previous studies, the researchers had shown that these two regions were smaller in poor kids, but that this physical change was reversible with proper nurturing from parents. The bad news here is that they found no evidence of this reversibility when it came to brain connectivity.

Still, that doesn't mean that there's nothing we can do. Last year, an unprecedented study in the US showed the incredible effect that a little extra income can have on poor children.

Four years into a research project that set out to monitor the mental health outcomes of low-income children living in North Carolina, a quarter of participating families unexpectedly started receiving an extra $4,000 per person annually. After two decades, the study revealed that, even given the small increase in income, the children in those families had far better emotional, behavioural, and mental health outcomes than their peers.

"Many things can be done to foster brain development and positive emotional development," said Barch. "Poverty doesn't put a child on a predetermined trajectory, but it behooves us to remember that adverse experiences early in life are influencing the development and function of the brain. And if we hope to intervene, we need to do it early so that we can help shift children onto the best possible developmental trajectories."

The research has been published in The American Journal of Psychiatry.